Abstract: Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic is a public writing course that was developed in response to an institutional call for a Public Pandemic Teaching Initiative in Summer 2020, which asked faculty to consider how this moment of radical disruption might inform our teaching and deepen our understanding of the relationship between writing, resilience, and response. The course provides a set of complementary, public-facing modules that offer teachers, community partners, and writers the tools to both write about and respond to writing about trauma. The resources, writing prompts, and activities draw from activities we have used in our undergraduate and graduate writing classrooms as well as our interdisciplinary research interests. Together, they support participants in addressing trauma from three perspectives: composing personal healing narratives; framing their personal inquiries within a larger research context; and positioning themselves within the larger community response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Public writing courses, such as Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic, demonstrate how interdisciplinary collaboration and accessible platforms can provide meaningful institutional responses during times of public health crises.

March 2020. As our department scrambled to move 200 classes fully online, we found ourselves trying to answer questions about accessibility for international students, planning for faculty sick leave, and wondering if our university would survive the economic fall-out of the pandemic.

In our own classes, we struggled to read how our students were processing the pandemic. Mya was teaching Introduction to Writing Studies when the announcement came—March 11, 2020 at 12:00pm EST—that the university was sending all students home. That day, she had planned to coach her students on how they would finish the semester at a distance. As she talked, one student announced the university closure email while another student reported a World Health notice that we were officially in a global pandemic. As Mya talked about the logistics of the course going forward, she struggled to convey to her students how much she worried about them as their lives were suddenly uprooted with so much uncertainty. How would we all survive this?

Laurie was teaching Advanced Writing for Health Professions when the pandemic news and university closure happened. That week, her students were working through a public writing unit, analyzing public-facing news sources for credible, reliable translation. Within days, as students struggled to find safe ways to get home or secure alternative housing, the class-wide discussions they had already started to have about the novel coronavirus and public health information from an interested distance became all too real. As hard-hit Boston-area hospitals braced for the possibility of surge capacity in early spring, some of these undergraduates who were on cooperative hospital rotations or working per diem while taking the class online found themselves on floors that had been turned into COVID-19 units. How could she even begin to talk about writing assignments or deadlines, knowing this?

Some of our colleagues jumped at the chance to teach about the pandemic. We were more reluctant. It seemed callous to invoke the coolly-distant academic approach in a world of trauma—of forced migration, mandatory quarantine, illness, and death. But we were buoyed by the response when our writing center’s annual Writers’ Week—a public outreach event with the neighboring community of Roxbury—was transitioned to a three-week online event in late April and early May 2020. Hundreds of people signed up for writers’ workshops and for help with resumé writing. Witnessing this desire to learn and connect, even if it meant connecting on Zoom, helped us see there was a space for more engagement with community-based trauma writing.

So, in May 2020 when the Northeastern Humanities Center in the university’s College of Social Sciences and Humanities announced the Pandemic Teaching Initiative—a library of publicly accessible educational modules that explore the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic—we were receptive to the idea of making public-facing materials for everyday writers. This reflective essay recounts our experiences in collaborating to build an online, open-access set of modules for the Pandemic Teaching Initiative on writing and trauma. Our article describes how we came to create public assignments—i.e., assignments meant to be taken up by teachers and students and everyday writers beyond our institution—and how our collaboration was shaped by our respective experiences. Like all our work in the COVID-19 pandemic, this set of modules is a work-in-progress in which we are still learning about the affordances and limitations of publicly accessible, free learning.

The Pandemic Teaching Initiative (https://cssh.northeastern.edu/pandemic-teaching-initiative/) was funded with support from the College of Social Sciences and Humanities Office of the Dean, the Northeastern Humanities Center, the Ethics Institute, SPPUA, and the NULab, and it was designed “to provide a growing set of resources that can be shared widely and combined flexibly in a variety of curricular and public contexts” (Northeastern University College of Social Sciences and Humanities 2020). The audience for the Pandemic Teaching Initiative included Northeastern faculty and students, colleagues and students at other institutions, and the public. Given the spirit of the initiative, faculty created week-long modules on topics that would be scholarly but also accessible, such as Why Markets Fail: The Economics of Covid-19; Religion in a Time of Corona; and Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Closed Borders: How the Covid-19 Pandemic is Impacting Displaced People. The content of the modules includes videos, lectures, panel discussions, interviews, or podcasts, background readings that are accessible to a non-specialist, and activities. To date, 25 modules have been created, and the module library is fully open for users to take the information as they wish. An analytics report on user traffic to the Pandemic Initiative website from October 1, 2020, to February 8, 2021, shows there have almost 7,000 page views with more than 5,000 unique page views. It remains to be seen if traffic remains consistent over time and which modules attract different kinds of audiences. Although there is a real need for open access information from universities and colleges, open-access learning initiatives remain uncommon outside MOOCs. The question remains which public audiences will be able to find the Pandemic Teaching Initiative. For our own module, we hoped teachers of writing would be a primary audience as well community members who might be writing in isolation.

In its call for proposals, the Humanities Center hoped this first-of-its-kind initiative would allow participants to use this moment of “radical disruption” to deepen and extend learning about relevant topics. From the start, we knew that we wanted our contribution to the Pandemic Teaching Initiative to tackle the topic of trauma. As teachers of writing, teaching through the pandemic has necessitated that we ask how we can use writing and response to trauma writing to help our students process these collective and personal traumas. Writing about physical and mental adversity and trauma can be a powerful tool for healing, as demonstrated as early as the late 1980s (Pennebaker 2018, 226). Recent research by John Evans and colleagues at Duke University suggests that expressive writing increases resilience and decreases perceived stress, depression, and rumination in study participants who experienced trauma (Glass et al. 2019, 246). The research consistently posits a powerful connection between expressive writing and healing, a connection that has informed how we teach writing students.

Over summer 2020, we developed a public writing course, Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic. The course is guided by the overarching question, “How can we transform the trauma we experience in the current COVID-19 pandemic into a reflective moment that inspires resilience?” Through complementary, linked modules we sought to design an accessible, public writing course that provides expressive, research, and community-based entry points. The three entry points were meant to give writers different ways of using writing to engage with their own questions about the pandemic. Some writers might want to write about their personal experiences. Some writers might want to learn about how to find research on COVID-19. And some writers might want to advocate for their own communities. As teachers of writing with experience in trauma-informed pedagogy and justice-based approaches to assessment, we marshalled readings and resources and paired them with activities to give writers multiple tools to write about trauma.

Our initial planning for Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic drew from Laurie’s Writing to Heal class, an undergraduate writing course she created as part of an interdisciplinary Health, Humanities, and Society minor. In that class, Laurie had developed a series of scaffolded, informal writing prompts, larger healing narrative essay prompts, and creative/digital healing projects. She found that frequent, low-stakes writing opportunities were especially helpful to students who wanted to compose longer healing narratives. This foundation became the first of three distinct entry points in the modules, the personal entry point, and informed the subsequent entry points for inquiry and community-based writing.

The personal entry point is for writers who wish to wrestle directly and privately with trauma. A key distinction is the type of writing that is produced; DeSalvo (2000) defines expressive writing as concrete, detailed, and that pairs emotions with events (pp. 22-25). Specifically, the material in this module follows a structure closely aligned with how writers approach trauma writing in her classroom: first, grounding in the research behind expressive writing and improved outcomes and the technical elements of expressive writing itself; next, analysis and discussion of published healing narratives within those frameworks; then, ongoing low-stakes expressive writing prompts; sharing writing for feedback and revision; and finally, the composition of fully developed healing narratives.

After discussions about how Mya could contribute to the project, we added an inquiry module. The inquiry entry point provides prompts that guide participants through the research process, including finding an orientation to a topic, asking a research question, finding and evaluating sources, and drawing insights from the research process. These activities help writers refine the analytic and translation skills necessary to bring self-generated research inquiries into the public sphere, whether for education, awareness, or call to action. The inquiry module drew on materials that Mya has produced in her Introduction to Writing Studies and scientific writing courses, especially around issues of self-reflexivity in the inquiry process and research ethics. She especially wanted to introduce writers to the topic of research ethics to give them a window into professional practice and underscore the importance of an ethical stance when pursuing COVID-19 inquiry projects.

We wanted to conclude Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic with a community-based entry point for writers who want to work with members of their own communities and provide a foundation for the skills, such as interviewing and writing advocacy-based genres, that are needed to engage in this type of community work. This entry point provided both of us ways to contribute and extend the work of the preceding inquiry module, so writers who had completed research inquiries could use this research in the public sphere. Here, we offered two paths. Laurie drew from her own experiences and national platform as a health and science writer to offer op-ed writing strategies and prompts. These activities also built off of an op-ed assignment her Advanced Writing in the Health Sciences students complete as a way of translating their research papers for a mainstream audience. Mya drew on her expertise as a qualitative researcher and complemented that expertise with research on interviewing trauma survivors to offer advice on interviewing for the purposes of oral history projects (Albarelli et al. 2020). For Mya, the oral history option came with the understanding that writers may well lose loved ones during the pandemic and capturing their words would provide a lasting tribute to family and community. Interviewing would be a way to stand witness to the effects of the pandemic.

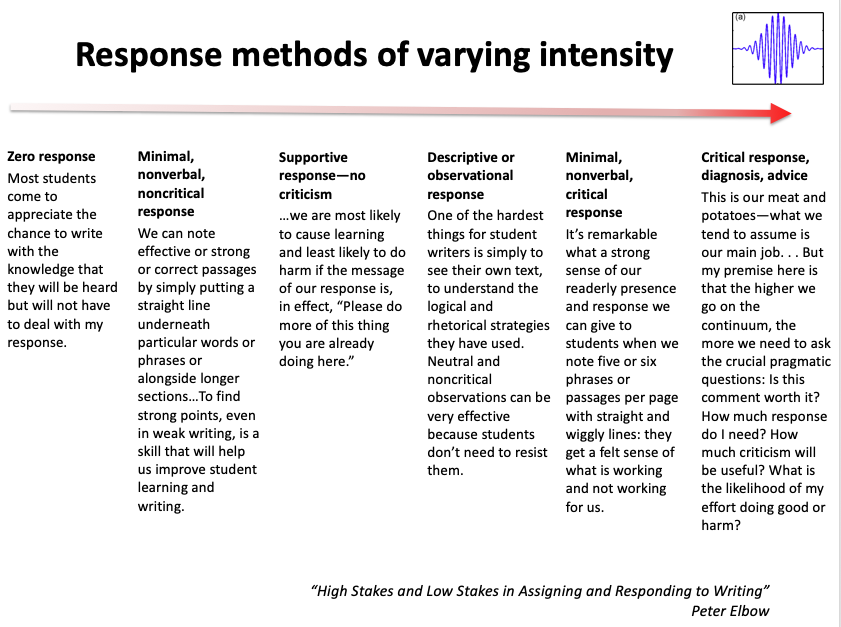

Beyond multiple entry points, another key feature of our project is the emphasis on responding to writing about trauma. Here is where we departed from what we had already used in our writing classes and instead, focused on knowledge acquisition ourselves. Much of the research on writing and healing focuses on designing writing activities, often private writing. Few studies suggest how we should respond to writing in which writers are working through traumatic events in personal writing, inquiry-based writing, or community-based writing. Even fewer studies suggest how we should respond together when both writer and reader share traumatic experiences. In this part of the modules, we offer five considerations for using formative assessment methods to respond to writing about trauma—(1) degree or intensity of response, ranging from no response to critical feedback (Elbow 1987, 1997); (2) focus of response, meaning that writers and readers negotiate the construct of trauma writing (DeSalvo 2000; Prior and Looker 2009); (3) medium of response, which invites us to consider what technologies we are using to respond to writing about trauma (Anson et al. 2016); (4) embracing self-reflexivity in responding to writers, especially when working with diverse populations (Anson 2000; Haswell 2006; LaFrance and Nichols 2010) as well as inviting self-reflexivity on the part of peers, community-members, and writers themselves.

Moreover, we felt an online bibliography on trauma and writing was necessary. Because the writing and responding to trauma lessons are grounded in the research on trauma theory, expressive writing and trauma, and trauma-informed responses to student work, we wanted to provide users with key insights from that literature. In addition to academic sources, we also provide popular resources (e.g., Teaching Tolerance; Poynter Institute; Health Story Collaborative; Health News Review; WHO and public health sites, etc.). We wanted to ensure writers had a variety of accessible resources available to them, resources that reflected the scope of content in the modules themselves.

As we designed Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic, we worked to bring together our different expertise in ways that would build off each other’s work. As such, the learning modules reflect our complementary backgrounds in health writing, public advocacy, empirical research methods, writing assessment, and social justice. Indeed, the scope of the modules themselves—from personal narrative writing prompts to research practices and interview strategies for oral histories to trauma-informed responses to writing—reflects these respective backgrounds. The work also made us reflect on our respective professional identities and the ways we needed to translate this project to university audiences.

For Mya, this project was an opportunity to apply research on writing assessment in programs and classrooms to community contexts. In doing so, it made her reflect on notions of justice—what does socially just writing assessment look like outside of the classroom? Outside of the classroom, writers may not have a community of writers with whom to share their work. Or they may work with readers who are eager to respond to their writing but are not quite sure how to respond to that writing. How do we honor the knowledge that community members bring as readers while also giving them language to talk about writing as more than grammar and form? Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic, also, gave Mya the chance to re-envision empirical research materials, such as interviewing techniques and research ethics, that she teaches in her undergraduate and graduate courses. It was exciting for her that she found ways to connect material from recent projects such as an interview by Sean Molloy with Marvina White on her experiences in the Search for Education, Elevation, & Knowledge (SEEK) program, a New York State higher education program offered at CUNY for students who need additional academic and financial support (White 2015).

For Laurie, this project gave her the opportunity to apply what she had learned from teaching several semesters of Writing to Heal in a way that tried to meet the urgency of the pandemic moment. A public-facing iteration of Writing to Heal would hopefully give writers from a wide range of backgrounds and interests the narrative strategies and frameworks to use expressive writing to foster resilience, and she was particularly interested in writers from marginalized communities having access to these tools. Given the different types of writing courses she teaches, she wanted to learn how best to help writers who have processed trauma through writing position their experiences and inquiries in research and advocacy writing contexts.

While we each brought complementary expertise to the project, we also wanted to grow and learn through this project. For Mya, Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic was a chance to learn more about the research on writing and trauma. As she discovered, much of the research on writing and healing does not engage with responding to author’s writing. Instead, writing is an end in and of itself. That “no-response approach” is valuable, but it does not translate very well into classroom contexts. Also, what about writers who want to channel their trauma into inquiry or public advocacy? Those writers need feedback on their writing, especially if they are speaking for an entire community. Additionally, how can we account for the ways that the COVID-19 pandemic is different for BIPOC writers and offer feedback that is attuned to those differences? This last question has become really important to Mya as she advocates for the inclusion of trauma-informed insights in anti-racist writing assessment.

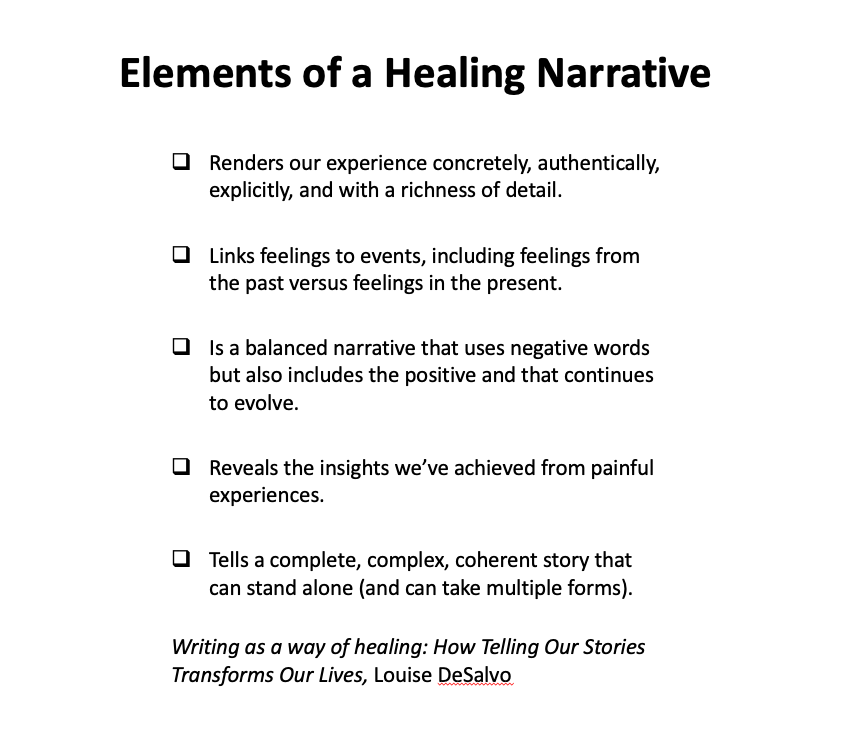

Like Mya, Laurie was also interested in learning more about the research on the response to trauma writing. She had established collaborative criteria based on Louise DeSalvo’s (2000) qualities of effective healing narratives with her undergraduate students, specifically that these narratives: (1) Render our experience concretely, authentically, explicitly, and with a richness of detail; (2) link feelings to events, including feelings from the past versus feelings in the present; (3) tell a balanced narrative that uses negative words but also includes the positive and continues to evolve; (4) reveal the insights we’ve achieved from painful experiences; (5) tell a complete, complex, coherent story that can stand alone and can take multiple forms (pp. 57-62). But what might response look like beyond the collaborative undergraduate writing classroom?

These interdisciplinary connections also speak to our relative positions and expertise within the university. For Mya, a tenured professor and director of the writing program, Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic was a goodwill effort, driven by a desire to learn, collaborate with Laurie, and translate her research expertise for a public audience. For Mya, the labor is professionally recognizable so far as it is a grant-funded project, but the actual publication of the project on the Pandemic Teaching Initiative resides outside a peer-reviewed journal, meaning that it does not have the kind of professional recognition that a scholarly publication has.

For Laurie, a full-time, non-tenure-track Teaching Professor in the Writing Program, Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic allowed her to combine her writing and advocacy expertise in the public sphere with her work in the classroom in a visible way within the university. She researches and writes about pain, gender, and chronic disease, and often publishes in the same narrative nonfiction genres her students are writing, so this project blends her active publishing work and her teaching in a new way. It also captured the often-unseen labor that goes into work like building new classes and developing new curriculum and interdisciplinary initiatives. For Laurie, the publication of Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic on the Pandemic Teaching Initiative was another demonstration of her teaching excellence. The additional recognition of that work through this publication on Prompt is translatable in the university hierarchy because it is a publication about teaching.

As we finished Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic, we reflected on the lasting trauma that has been felt by individuals as they, their families, and communities struggle during this historical time. While an immediate goal of the project was to make this content for writing about the pandemic public, the activities, prompts, and strategies contained in these modules offer utility beyond COVID-19. The resources here will be helpful as we transition into a larger vaccination phase and, eventually, a post-COVID landscape, whatever that may look like. In our writing classes and program workshops, we have seen writers use these methods for writing about physical and mental illness, relationship and family trauma, addiction, and other circumstances not strictly related to COVID-19 where the ability to write about events helps process them.

We have used many of these assignments and resources in our own undergraduate and graduate classes and know their suitability for students in this setting. We envision these public-facing modules as useful to students, teachers, and writers outside of higher education as well, from high school students to lifelong learners. Writers who wish to take the step to publish their work, whether a written or oral healing narrative, research inquiry, or community-based advocacy project, will have resources to do so. We also see these tools and skills as useful to community partners, nonprofit organizations, and groups working with marginalized or underserved communities.

Mya’s Fall 2020 graduate seminar Writing and Teaching Writing included materials on trauma-informed pedagogy. Her students found that material especially relevant as they developed sample syllabi for future writing classes. In spring 2021, Mya used the oral history materials from Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic in her Introduction to Writing Studies course. In spring 2020, her class began, as it usually does, with an archival research unit. Her spring 2021 students did not have access to the Northeastern University physical archives, but they did have access to the deep funds of memory from their own community members. As the pandemic continues to ravage communities and the death toll climbs higher, it feels especially critical to gather stories from people we love.

Laurie’s Spring 2021 Writing to Heal included more focus on oral storytelling and health narratives, and she integrated the advocacy/op-ed writing assignment to the course as well. Students expressed interest in reading more of the research behind expressive writing and healing and have benefited from the online bibliography associated with this project. Some used those resources to connect their personal writing to research inquiries in their science-based classes. Eventually, Laurie hopes to develop a stand-alone advocacy writing course. With a fellow Northeastern colleague, she used these expressive writing strategies to run a second series of trauma writing workshops for teens at Boston’s John D. O’Bryant School for Mathematics and Science in May 2021, in collaboration with literacy nonprofit 826 Boston. This type of community engagement and expansion of writing in the public sphere speaks to the overall aims of our curriculum.

More than a year after our university moved online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we are still wrestling with what the pandemic means for us and our students. We struggled through fall 2020 and watched our students flag from fatigue, stress, and depression, and saw much of the same in our spring 2021 semester. In the Boston community, COVID-19 death is very real. As of May 24, 2021, there have been 70,529 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Boston and 1,382 deaths (Boston Public Health Commission n.d.). The community next to Northeastern is Roxbury. Roxbury has one of the highest rates (11.8%) of current community positivity in the city (Boston Public Health Commission n.d.). Understanding how to process the trauma that we are living through will be essential to healing for our students and the Boston community. Writing can be a way to process that trauma and heal. Research tells us this. As teachers, we have seen firsthand how using expressive writing—writing that is concrete, detailed, and links events with emotions—helps students develop as stronger writers and allows them to process traumatic experiences in productive, meaningful, and often, empowering ways. We have seen how inquiry-based projects that are driven by writers’ own interests are some of the most meaningful writing that students do. And we have seen how community-based approaches can be a chance to give back to the communities from which we come.

Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic is an attempt to bring together what we know and what we teach so that writers across ages, experiences, and educational experiences can use personal experiences, research, and community-based responses to heal.

Laurie Edwards and Mya Poe

NOTE: The course materials published here are also available via the Northeastern University Pandemic Teaching Initiative at https://cssh.northeastern.edu/pandemic-teaching-initiative/writing-and-responding-to-trauma-in-a-time-of-pandemic/

Living through the current pandemic is not only about the medical and financial fall-out of COV-SARS-2 and COVID-19 illness, but also about the lasting trauma that has been felt by individuals as they, their families, and communities struggle during this historical time. Storytelling is a means of healing from trauma. These modules give writers tools to compose personal healing narratives, to frame their personal inquiries within a larger research context, and to position themselves within the larger community response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, we draw upon research on trauma theory, research on expressive writing and healing, and research on responding to writing. Through this public teaching initiative, we ask “How can we transform the trauma we experience in the current COVID-19 pandemic into a reflective moment that inspires resilience?”

1. any disturbing experience that results in significant fear, helplessness, dissociation, confusion, or other disruptive feelings intense enough to have a long-lasting negative effect on a person’s attitudes, behavior, and other aspects of functioning. Traumatic events include those caused by human behavior (e.g., rape, war, industrial accidents) as well as by nature (e.g., earthquakes) and often challenge an individual’s view of the world as a just, safe, and predictable place.

2. any serious physical injury, such as a widespread burn or a blow to the head. —traumatic adj.

All the modules in this series are based on the following four principles of trauma-informed care and teaching:

Connectedness—valuing of relationships

Protection—ensuring safety and trustworthiness

Respect—promoting choice and collaboration

Hope—Resilience and Change

(Adapted from Hummer, Crosland, & Dollard, 2009)

Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic includes the following components:

Three complementary modules with sessions, resources, and activities that explore writing about trauma and responding to writing from multiple perspectives:

The personal entry point with personal written and oral healing narratives

The inquiry entry point for writers who want to pursue self-generated research inquiries related to COVID-19

The community entry point, which supports writers as they position themselves within larger community responses to COVID-19

A comprehensive online bibliography on trauma, writing, and response

These modules were created as part of Northeastern University’s College of Social Science and Humanities Pandemic Public Teaching Initiative. The Pandemic Teaching Initiative, which is supported by the CSSH Office of the Dean, the Northeastern Humanities Center, the Ethics Institute, the SPPUA and the NULab, seeks to create a library of publicly accessible modules that explore topics related to pandemics and their disruptions and impacts.

All of the prompts will generate material that will be shareable, if participants wish, during an open, online event series.

Caution

We have attempted to limit traumatic content in the main text of this module, but the examples used in the following modules may be disturbing for some individuals. Examples include sexual violence, racism, COVID-19 illness and death.

Laurie Edwards is a Teaching Professor in the Writing Program and Online Pedagogy Coordinator for the English Department. She primarily teaches ENGW 3306, Advanced Writing for the Health Professions, and ENGL 2770, Writing to Heal. Her teaching and expertise in online learning have been recognized by the College of Social Sciences and Humanities Outstanding Teaching Award. She is an author of two books on chronic illness: Life Disrupted (Walker, 2008), a Library Journal Best Consumer Health Book, and In the Kingdom of the Sick: A Social History of Chronic Illness in America (Walker, 2013), a Booklist Editor’s Choice for 2013. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Boston Globe, NPR, and many other outlets, and she has appeared on Fresh Air with Terry Gross and The Today Show with Maria Shriver to discuss gender and pain.

Mya Poe is an Associate Professor in the English Department and Director of the Writing Program. Her research focuses on writing assessment and writing development with particular attention to equity and fairness. She is the co-author of Learning to Communicate in Science and Engineering (CCCC Advancement of Knowledge Award, 2012), co-editor of Race and Writing Assessment (CCCC Outstanding Book of the Year, 2014), and co-editor of Writing Assessment, Social Justice, and the Advancement of Opportunity (2019). Her scholarship has appeared in journals such as College Composition and Communication, The Journal of Business and Technical Communication, The Journal of Writing Assessment, and Assessing Writing. She has also guest-edited special issues of Research in the Teaching of English and College English dedicated to issues of social justice, diversity, and writing assessment. She is series co-editor of the Oxford Brief Guides to Writing in the Disciplines. Her teaching and service have been recognized with the Northeastern University Teaching Excellence Award, the Northeastern College of Social Sciences and Humanities Outstanding Teaching Award, and the MIT Infinite Mile Award for Continued Outstanding Service and Innovative Teaching. She is a board member of the Journal of Writing Analytics, Assessing Writing, Written Communication, Journal of Writing Assessment, and Research in the Teaching of English.

I think of narrative as storytelling: that is, as a way of ordering events and thoughts in a coherent sequence that makes them interesting to listen to. It therefore has a strong oral heritage. The sequence doesn’t have to be strictly chronological, though it can be; it can include digressions and flashbacks and foreshadowings, just as a story recounted around a campfire can. But because narrative is powered by events, its goal is not essentially analytical or critical — though, like many stories (especially in traditional genres — folktales, fairy tales, fables), it can contain substantial moral lessons.

—Memoirist, essayist, and editor Anne Fadiman,

as interviewed by Chip Scanlan for Poynter’s What is Narrative, Anyway?

This module offers an overview of expressive writing and storytelling as a means of healing. This module follows four steps:

Identify the basic research supporting expressive writing and identify core elements of it.

Identify narrative strategies and discuss examples of types of healing narratives to help you better understand the narrative techniques and strategies you will incorporate.

Complete informal writing prompts that offer you the opportunity to begin applying these strategies to your own writing.

Use informal writing prompts to build towards a full-length healing narrative and recognize elements of effective feedback.

This session offers an overview of expressive writing, which is writing that pairs emotions with events and action with reflection. It also offers some of the research into writing about trauma as a means of healing, as well as examples of published written and oral healing narratives. This basic grounding in the literature of expressive writing and healing will support the specific narrative entry points for writers that appear in subsequent modules.

Expressive writing is a specific type of narrative writing that combines experiences with reflection and insight. Often, we’re more familiar with straight journaling or chronicling events in a diary, but it is the interplay between emotions and events and the ability to distinguish feelings from the past and the present in expressive writing that distinguishes it.

Expressive Writing

Does more than simply record events

Does more than simply vent feelings

Includes action and reflection

Includes descriptive and/or figurative language

As defined by Louise DeSalvo, Writing as a Way of Healing, 2000, Chapter 2.

James Pennebaker, The Expressive Writing Method

What Does Expressive Writing Look Like?

Glass, et al. “Expressive writing to improve resilience to trauma: A clinical feasibility trial.”

Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, vol 34, 2019, pages 240-246.

Pennebaker, James. “Expressive Writing in Psychological Science.” Perspectives on Psychological Science, vol 13, no. 2, 2018, pages 226–229.

Kimberly Mack, “Johnny Rotten, My Mom, and Me”

Tracy Strauss, “Writing Trauma: Notes of Transcendence”

Ann Wallace, “A Life Less Terrifying”

Sean Manning, “My Brain Explosion” (audio story)

“….when people transform their feelings and thoughts about personally upsetting experiences into language, their physical and mental health often improve.”

“…having people write about emotional upheavals can result in healthy improvements in social, psychological, behavioral, and biological functioning.”

“Most writing groups are asked to write about assigned topics for 1–5 consecutive days, for 15–30 minutes each day. Writing is generally done in the laboratory, with no feedback given.”

—Pennebaker, J.W. & Chung, C. (2011). Expressive Writing: Connections to Physical and Mental Health. The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology

This kind of writing does seem to work best for people who find themselves thinking about, obsessing about, worrying about, dreaming about emotional upheavals that have occurred in the past.

If it’s been a major traumatic experience that’s happened in the last few days, maybe even weeks, writing may not be good for you . . . We don’t have sufficient defenses immediately after a trauma.

The people who benefit the most are the ones who on the first day of writing often have almost a stream of consciousness or almost a random series of events, and over the course of the writing, they start putting it together, constructing a story out of it.

—Moran., M.H. (2013). Writing and Healing from Trauma: An Interview with James Pennebaker, composition forum, 28

Caution:

“The notion that not all psychotherapeutic interventions are equally efficacious across cultural groups has been articulated for decades (Sue & Zane, 2006). However, a review of cultural competency in psychotherapeutic interventions noted that little is known about whether individuals from a given ethnic community would respond poorly to certain evidence-based approaches, and thus little consensus exists as to when to use cultural interventions (Sue, Zane, Hall, & Berger, 2009).

—Gallagher, M.W., et al. (2018). The unexpected impact of expressive writing on posttraumatic stress and growth in Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74, p. 1673–1686

Once you’ve read the essays and articles and watched the two videos that accompany this session, think about how expressive writing is different from other types of writing you may have done (journaling, expository writing, etc.). What do you see as the biggest opportunities and challenges of this type of writing?

In this session, you will learn about three specific types of wounded body/healing narratives as classified by Louise DeSalvo: the chaos narrative, the restitution narrative, and the quest narrative. The suggested readings offer elements of these types of healing narratives. In addition, the Strauss piece offers a useful frame for how to pair emotion with reflection/insight in expressive writing, which you will be able to apply to your own writing in the next session.

Dr. Alison Rosalie Brookes, “Love and Death in the Time of Quarantine”

Nina Collins, “Graduation”

Tracy Strauss, “Notes of Transcendence #4: The Situation and the Story”

Jennifer Stitt, “Will Covid-19 Strengthen Our Bonds?”

Adina Talve-Goodman, “I Must Have Been That Man”

Jesmyn Ward, “On Witness and Respair: A Personal Tragedy Followed By a Pandemic”

“One reason, then, to write as we face these critical junctures in our lives is that illness and disability necessitate that we think differently about ourselves, about everything. Writing gives us back the voices we seem to lose when our bodies become ill or disabled…writing helps us assert our individuality, our authority, our own particular style…”

—Louise DeSalvo, Writing as a Way of Healing, 182-183.

“People who write about their loved ones’ deaths are paradoxically engaged in a search for the meaning of their loved ones’ lives. They want to make a record; they want to describe their loss and grief. But they want to discover, too, an overarching meaning for this death…”

—Louise DeSalvo, Writing as a Way of Healing, 191.

Louise DeSalvo, Writing as Means of Healing, Chapter 10

Chaos Narrative

There is no coherence or sequence; scenes are consciously disjointed

There is an immediacy to events as they unfold in real-time without processing

These narratives can be difficult to read and write and threatening to readers because there are no happy endings

Restitution Narrative

We welcome them because they tell of recovery, of adversity that has been overcome

They imply that bodies and lives can be restored to what they were before a trauma

Many assume the genre to ultimately critique the culture of recovery/fighting the good fight that we expect

Quest Narrative

They represent a search for something to be gained through the experience or journey of illness or trauma

They assert that everything is always changing and we can still live meaningful lives in the face of trauma and adversity

They strive for accuracy and unflinching detail

They can put experience to good use and for greater advocacy/activism

Often, healing narratives have elements of more than one of these frameworks—for example, particular passages in a quest narrative may take on the immediacy and visceral feel of a chaos narrative. You will likely identify elements from more than one of these frameworks in the published essays in this session.

Once you’ve read the essays, think about which types of healing narratives (chaos, restitution, and quest) you would characterize them. Which sample essay or essays resonate the most with you, and which narrative elements/strategies account for that—can you point to specific moments or language in the text?

In this session, you can apply what you’ve learned about different types of healing narratives and from the sample published essays to formative writing activities. Please choose as many of these short, informal writing exercises as you would like, keeping in mind the fundamentals of expressive writing, i.e., linking emotions with events. Start with 15 minutes on a prompt and see how far you get.

As Ann Wallace asks in “A Life Less Terrifying,” write a journal entry about a time when you were denied some kind of essential or fundamental human need—love, compassion, respect, dignity, shelter, the possibilities are many. If you’d like, you can focus this within the context of COVID-19 and your experiences living through it.

Thinking about a time you were denied a fundamental need, now try writing a letter to someone as a means of telling this story. Think about the differences in your story that arise when you address this towards an intended reader.

Draw a map of a meaningful landscape from your COVID-19 experience (e.g., where you’ve spent the most time) including as many details as possible. Think about 2-3 specific memories/events that have taken place in that space, and make a list of as many sensory details as possible—what sounds, smells, touch, images, etc. do you associate with this place and these memories? Use this sensory list to start writing about your experiences during COVID-19.

What family story or generational tale do you wish had a different ending? What would it look like? Alternatively, what COVID-19 story would you re-write if you could?

Looking for additional short prompts specific to COVID-19? Check out The Pandemic Project, directed by James Pennebaker.

Have a response to a writing prompt you want to deepen? Consider using Strauss’s Situation and Story essay for the following activity: Make a two-column chart where you identify the actions/plot points in your narrative (the situation) and a column where you reflect on the emotions of the event (the story). This will help highlight places where the pairing of emotions with events and action with reflection could be developed.

We’ve discussed the different kinds of healing narrative classifications (the chaos narrative, the restitution narrative, and the quest narrative), and have read a variety of narratives that deal with trauma, loss, illness, etc. To draft your own healing narrative, take these three frameworks and the formative writing you’ve done in Session 1.3 surrounding this denial of a fundamental need as a foundation for a longer essay where you explore a seminal event or trauma in your own life. If you would like to focus this writing on events related to COVID-19 you may, but you are not limited to that. As you write, think about the qualities of healing narratives DeSalvo mentions, and the characteristics/criteria for successful healing narratives included in this session. Above all, healing narratives pair emotions/feelings with events.

Once you’ve drafted your healing narrative using the prompt above, we recommend getting feedback on it so you can continue to deepen and order the draft.

You might find that you want to share your narrative with someone you trust or even present your narrative in a public forum. Before you share your work, however, you want to think about the feedback you may receive.

Because most readers are not familiar with healing narratives, it’s useful to give them some guidance on how to respond to your writing. Two tips are helpful here:

Content-based response. Based on the research and work of Louise DeSalvo, ask readers to focus on the following characteristics of effective healing narratives.

Intensity of response. Rather than having readers give you critical response or diagnosis, readers might offer supportive response to help you build on what you are already doing well.

“African Americans are at much higher risk of contracting COVID-19 than the rest of the population, and they are much more likely than white people to die from the virus.”

—Michael Ollove & Christine Vestal, “COVID-19 Is Crushing Black Communities. Some States Are Paying Attention”

While individuals find it therapeutic to write stories or narratives about their personal experiences related to COVID-19, other individuals find it helpful to learn more about the disease and its implications. Inquiry-based writing is a powerful way of harnessing the potential of research to answer the questions that most interest you.

This module will offer participants who want to process the implications of the pandemic through research. Activities in this module guide writers through the research process. These activities help writers refine the skills necessary to bring self-generated research inquiries into the public sphere, whether for education, awareness, or call to action. This module follows four steps:

Identify what inquiry is and types of inquiry-based writing.

Generate and evaluate inquiry questions.

Find and evaluate scholarly and popular sources on COVID-19.

Translate health/science information accurately and responsibly into an essay, report, or presentation.

Like the first module on narrative writing, inquiry-based writing starts with your values, your experiences, and your goals and interests, and that is what you will focus on in this module. This first session will cover the basic considerations of inquiry-based writing, before we move into generating questions and drafting your own research inquires.

Inquiry is the process of asking questions to solve a problem. In education, inquiry-based learning is a way for students to generate research questions for further study and, thus, model the work of professional researchers. In this way, teachers become guides for students, rather than assigning research topics.

“With inquiry-based learning, teachers present problems for students to work on before students are taught the key ideas that will help them solve the problems. Learners draw on previous knowledge to deduce the principles at play. They use their own language to describe what’s going on before being given academic terms.”

—Anne-Marie Womack, Director of Writing at Tulane University

Inquiry-based writing instruction has been shown to provide more meaningful learning for students and keep students engaged. In inquiry-based writing, students can draw on personal connections in their writing and research (Eodice, Geller & Lerner, 2016; Eodice, Geller, & Lerner, 2019). When combined with clear expectations for writing and the opportunity for supportive feedback from a peer, such activities lead to deeper learning and personal development (Anderson et al., 2016).

Inquiry-based writing can be a potentially positive way to address trauma because it gets writers to focus on action. It is a way to build resilience.

Too often it is assumed that someone who has been sexually abused can only write about it as a purely emotional, psychically traumatic experience....While some survivors may only feel comfortable writing about their abuse within a class focused on personal essays, they are not necessarily ‘deterred,’ as it were, from addressing these issues in a class focused on academic, critical, nonpersonal genres. ..In fact, [students want to write] about their abuse in a researched essay, [structuring] their texts to move, either implicitly or explicitly, from often hauntingly detailed or powerful understated narratives of the abuse to analyses of how it has affected their relationships with others and themselves, as well as generalizations about what such abuse suggests to them about families, American culture, genre, and power relations”

—Michelle Payne, “A Strange Unaccountable Something;

Historizing Sexual Abuse Essays”

Dr. Louise Aronson, “Story as Evidence, Evidence as Story”

National Library of Medicine, “Responsible Science: Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process”

Carl Zimmer, “How to Read Coronavirus Studies, or Any Science Paper”

Lily Rubin-Miller, Christopher Alban, Samantha Artiga and Sean Sullivan, “COVID-19 Racial Disparities in Testing, Infection, Hospitalization, and Death: Analysis of Epic Patient Data”

Ed Yong, “The Core Lesson of the COVID-19 Heart Debate”

Deli O’Hara, “Sport psychologists grapple with worried athletes during COVID-19”

Inquiry-based research is driven by the ongoing relationship between asking questions, seeking information, and refining the questions based on what you find. In this session, you will find resources and activities to help you frame your questions. From there, you can work on activities related to data gathering and data analysis.

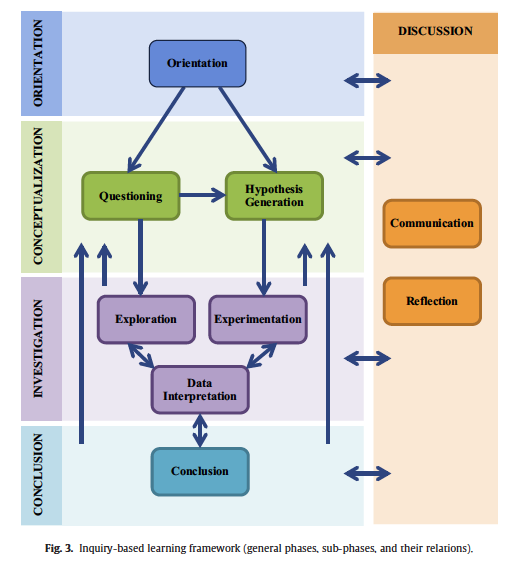

Inquiry-based research typically includes four phases: (1) orientation, (2) conceptualization, (3) investigation, and (4) conclusion. Discussion happens throughout the process.

(Pedaste et al., 2015)

Orientation. As shown in the figure above, inquiry-based research starts with orienting yourself toward a topic. In other words, you want to find a topic to write about.

Orientation questions:

Using some of the COVID-19 healing narratives you composed in Module 1, or using your personal experiences living through the pandemic thus far, consider if there are potential research topics you can extract from these personal narratives.

What are some COVID-19 topics that interest you?

Why are you interested in those topics?

Why are they relevant to your personal and/or professional experiences?

What is your ultimate goal? Do you want to write an op-ed, give a public talk, write a research article, or something else?

At this early stage in the research process, we ask about your ultimate goal. That’s because no professional researcher waits until the end to think about writing. In fact, what we want to write often shapes how we go about conducting research, including how much research we do and what kinds of sources we use. For example, if we want to write an op-ed, we might only need 5-8 good sources. On the other hand, if we want to write a research article, we might need 20 or more sources.

Discussion: Often it is helpful at the beginning of a project to discuss your ideas with someone else. Talking to someone else can help you identify what really interests you. You can even brainstorm new ideas with a friend.

After orienting yourself to a topic, take a step back. When working on trauma-informed inquiry, we recommend some introspection before proceeding with your research. Professional researchers call the process of examining our own values, goals, and beliefs in relation to our research and teaching “reflexivity.”

“No longer is it acceptable to be the omniscient, distanced qualitative writer… How we write is a reflection of our own interpretation based on the cultural, social gender, class, and personal politics that we bring to research…All researchers shape the writing that emerges”

(Cresswell, 2007, p. 178-179)

Besides being helpful in understanding your values, goals, and beliefs in relation to your research, self-reflexive exercises can also help you think about the impact of your search on readers.

Self-reflexive questions:

Why do I find this topic personally interesting?

How does my identity impact my research interest and the ways I might answer my research questions?

What potential harm might I do to myself by conducting this research? Are there triggers that I should consider before starting?

What do I hope will come of my research? What will I do if I do not get the response that I hope for?

Who might be helped by my research? Who might be harmed by my research?

Who do I want to read my research? Why them? What do I hope will be their reaction?

Tip: Keep a research journal that includes the personal story of your research along with information about sources and data.

Conceptualization. Conceptualization is a complicated way of saying “asking questions” and generating some ideas (or hypotheses) about what you might find through your research. The trick to making inquiry-based research “good” is in asking good questions. A good research question is personally meaningful, accessible, and answerable. See Table 1.

| Criterion | Question | Explanation |

| Personally Meaningful | Does this research result in something that you care about? | Research is time intensive. For that reason, you want to ask a question that you find personally compelling. A personally compelling question will give you the impetus to pursue your project over time. |

| Accessible | Is the question the right scope? Can you actually accomplish what you set out to do? | A good research question is one you can pursue with the time and resources you have available. All of us have limitations on our time and access to information. When we ask research questions, we want to try to make our inquiries successful by. understanding those time and material limits. That often means scaling back our research questions to something more modest. |

| Answerable | Can you find sources to answer your research question? | There is a lot of research out there. Often it is a matter of learning how to find that information. See (3) Investigation for research tips. Not all research questions are answerable. That’s OK. In fact, some researchers have started to talk about “missing data sets.” Consider this: A good research question allows you to determine if research exists or not to answer your question. |

Asking questions activities

Using the research topics you generated in (1) Orientation, begin to generate some research questions.

When you begin to generate research questions, don’t worry about good grammar or logic. Instead, try to think of as many questions as you can. Here are some to get you started:

What topic is it that you want to learn?

What is known about this topic?

Who does this topic affect?

What are some of the issues of conflict surrounding this topic?

What are some aspects of your topic that are unknown right now?

What might be some outcomes or uses of your inquiry?

Using the fake news/fact-checking sites and the resources on how to find scholarly sources, briefly, how is the topic being discussed in popular and academic circles right now?

Example: If you are a parent, you might want to learn more about the effects of COVID-19 on children. Your original question might be:

What do I need to know about COVID-19 and children?

With such a broad question, you might find yourself overwhelmed. To narrow your topic, consider a narrower question, such as:

What are the symptoms of COVID-19 in children?

How are infants affected by COVID-19?

How are school age children affected by COVID_19?

What are COVID-19 infection rates among children?

How are infants who test positive for COVID-19 cared for?

After you generate a list of potential research questions, ask yourself:

How passionate do I feel about this topic? Who am I accountable to in doing this research? Am I doing this research for myself or someone else?

Can I narrow my topic by age, time, geography, or some other way? What keywords are central to my research? For example, can I change generic words like “people” to specific words like “infants” or “senior citizens”?

What sources might I be interested in reviewing to answer my question? What do I expect to find?

With the questions above as a frame, write a brief paragraph in which you narrow the focus and specify your inquiry issue/topic.

Tip: You will likely find you need to continue to narrow your focus, so a willingness to evolve with an idea is an important characteristic to keep in mind. It’s also helpful to think about what you might find as an answer to your research question. Thinking about the kinds of evidence you might find will help you revise your research question. For example, a question about infection rates will likely generate quantitative evidence—that is, lots of numbers. On the other hand, a question about how medical school students are training during the COVID-19 pandemic might result in stories. In fact, professional researchers often do a little research to see what kinds of sources are available on a topic and then go back and revise their research questions.

Investigation. Now that you have a working research question, it’s time to start finding research. Adding research to your writing is a way to provide more context for your discussion and build your ethos as a writer. And it’s a great way to learn. “Sources” can include everything from newspapers and online forums to peer-reviewed scientific articles. Academic research, such as scientific articles, are published in “journals,” such as The New England Journal of Medicine.

Academic sources = books published by academic presses, peer-reviewed journals

General sources = newspapers, magazines, blogs, television, and radio (LaVaque-Manty & LaVaque-Manty, 2016, p. 153)

Collecting sources.

While a Google search will certainly generate a lot of information, it may not be the best information to answer your research question. Google searches take you to all kinds of websites, ranging from reputable research sources to idiosyncratic blogs. Google Scholar is a bit better but can often produce results that are difficult to filter and sort. Professional researchers use academic databases to locate “peer-reviewed” research.

Peer-reviewed research is research that has been evaluated by other professionals in a field. Often, reviews are done anonymously so researchers are not influenced by the identity of the research team submitting their work for review. Likewise, authors typically do not know the names of their viewers. This process is known as double-blind peer-review” and professional researchers believe that such a review process leads to more objective analysis of articles to be published in journals.

The Northeastern University librarians have put together a video series on how to find academic sources. For example, in this series, they discuss how to use a search engine called Scholar OneSearch to find academic research articles. In this series, they explain how to improve your search strategies and find ebooks.

Beyond academic sources, government sources are really valuable in finding public health information (Note: government websites always end in .gov). In fact, many professional researchers regularly use websites like the Centers for Disease Control website to find information about disease rates. In addition to federal websites, states often have local information available on their websites. For example, this website has Massachusetts-specific information.

Tip: Academic databases can tell us what research has been published but they don’t always give us access to the articles.

If you are a Northeastern student, you can access many articles directly from the Scholar OneSearch page.

If you are not a Northeastern student, you can use Scholar OneSearch to find articles. You can then perform a Google search to find the original article.

For example, in our research on the care of infants who test positive for COVID-19, we found the article below by using Scholar OneSearch. As a Northeastern student, we can simply click on the link that says “Download PDF.” As a non-Northeastern student, we have a slightly different path to find the article.

By copying the name of the article and entering it into Google, we can see various links to the article. The second link, which comes from the National Institutes of Health, actually has a free download of the article.

Before the COVID19 pandemic, many academic articles were behind a “firewall,” meaning you had to pay to get access to the article. However, many academic journals have now provided free access to COVID-19 research in an attempt to help the public learn more about the disease.

Analyzing sources. How do you know whether a source is reliable or not? In general, academic sources are better than non-academic sources when you are conducting research. Professional researchers evaluate the quality of sources by looking at a few key markers:

Type of source

Author expertise

Publication date

Publication venue

Research quality

The Northeastern library has excellent guides on how to evaluate sources, including data and statistics.

Fake News and Fact-Checking COVID-19 Sites

You can find a lot of incorrect information on COVID-19 on the internet. Below are some resources to help assess your sources.

Facts in the Time of Covid-19

Fake or Real? How to Self-Check the News and Get the Facts

False, Misleading, Clickbait-y, and/or Satirical "News" Sources

How To Avoid Misinformation About Covid-19

Poynter International Covid-19 Fact Checking SiteInvestigation activities:

Now that you have collected some sources on your topic, it’s time to review them critically before writing up your research. What kinds of sources has your search yielded? What information is provided in those sources? What information do you still need?

For each source, ask the following questions:

What is this source—for example, a blog, scientific study, op-ed, or government report? Is it relevant? What genre is it? Is this source based on opinion or facts?

Who is the author? What expertise do they possess?

When was the article published? Does it contain timely information?

Where was the source published? Is that a reputable journal or impartial news source? If it is a scholarly source, does the journal have an impact factor—that is, an indicator that other researchers cite research from the journal? Has the article been cited? Was it peer reviewed?

How was the research conducted? Where was the research conducted?

After reflecting on the results of your research and what that research has yielded, you may decide to go back and do some more research. Try finding new sources if you cannot answer the questions above. Also, it’s not uncommon to find gaps in your research at this stage. You may need to go do more research, if you haven’t found exactly what you need to answer your research question.

Discussion: At this point in a research project, it’s very helpful to talk to someone about your research. By explaining what you are researching and what you have found, you are synthesizing your research findings into chunks of information. That chunking will help you both process what you have learned and help you consider what else you might want to know.

Conclusion. After you have found and analyzed sources to answer your research question, you need to figure out what to say. Professional researchers sometimes call this a “story,” and many professional researchers talk about the “story” of their research. A good research project reads like a story—there is a question, a search for answers, and …. ANSWERS!

In her JAMA commentary, Dr. Louise Aronson writes, “With a frequency and consistency that should make those who question the role of anecdotes in medicine and science rethink their position, a single, well-told story of human suffering trumps the most eloquent explanation of a large-scale trial...Mounting data, and the entire historical record across cultures and continents, suggest that human beings are uniquely wired for stories and that stories, with their linking of the cognitive with the emotive, are often both more memorable and more persuasive than other sorts of information” (1694-5).

So, how do you tell a good story with all the information you have found?

One way is to use a storyboard. There is no one right way to make a storyboard. It can be as simple as bullet points, a traditional outline, or a series of images. A storyboard also helps you figure out where you need research in your story. Afterall, no one wants to read a series of research summaries. Readers want a presentation, essay, or report that is punctuated with research findings.

Storyboards are used in film-making and other creative arts to provide a high-level visual roadmap.

Once you figure out where you want to add research in your presentation, essay, or report, you need to decide how you will use that research. There are three main ways that writers include research: summary, paraphrase, and direct quotation.

(LaVaque-Manty & LaVaque-Manty, 2016, p. 155)How to Summarize

Summarizing involves a specific process of converting what you have read into a much shorter version. The process can generally be handled in four steps:

1. Identify the main claim and write it in your own words. Often, you will find it easiest to write this if you read the abstract, introduction, and conclusion of an article. The main claim is usually most developed in these sections. If someone were to ask you, “What is this about?” this statement would be your answer.

2. Explain the main arguments that support this claim. You can omit aspects that are not central to supporting the claim, such as specific details or examples.

3. Include necessary context. Sometimes a small amount of context, such as the circumstances of the research, can be helpful to understanding the claim or conclusions.

4. Avoid personal opinion or interpretation of the original. This point holds true for students working on summary assignments for school but may be “bent” in professional writing, depending on the purpose and audience. (Irish, 2015, p. 209-210)

Make sure that if you are summarizing, paraphrasing, or quoting someone else’s ideas or words that you cite your source. Usually a citation includes an in-text reference and an entry in a References page. The Northeastern University guide to citing sources is a good resource for learning the different ways of using sources.

Tip

Professional researchers typically avoid sweeping statements like, “No research exists on the effects of COVID-19 on patients with thyroid conditions.” Why? Because there is so much research published every year that it is impossible to know every study that has been completed. Instead, researchers tend to “hedge” by saying something like, “Little research exists on the effects of COVID-19 on patients with thyroid conditions” or something even more honest like, “Our research yielded no current studies on the effects of COVID-19 on patients with thyroid conditions.”

Caution

The desire to tell a good story with data, however, sometimes leads researchers to commit research misconduct. Lessons from the scientific world on research misconduct can be helpful guides for anyone conducting research.

Definition of Research Misconduct:

Research misconduct means fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism in proposing, performing, or reviewing research, or in reporting research results.

Fabrication is making up data or results and recording or reporting them.

Falsification is manipulating research materials, equipment, or processes, or changing or omitting data or results such that the research is not accurately represented in the research record.

Plagiarism is the appropriation of another person’s ideas, processes, results, or words without giving appropriate credit.

Research misconduct does not include honest error or differences of opinion.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Research Integrity

Conclusion activities:

Now that you have found good sources that help you answer your research question, it’s useful to take a step back before writing up your findings. At this moment, you are “close” to your work, which means that you may not see gaps or strengths in your research process. Talking to a friend can help you get some perspective. The following questions can also help you self-assess your work:

What are the main themes, ideas, or findings that I find most compelling from my research?

What assertions can I support with the sources I have found? Do multiple sources support those assertions?

Have I answered my research question? If not, do I need to change my original research question?

How do I feel about this research? Have I learned something? How has that new knowledge changed me?

What might happen based on my research? What might be a positive effect? A negative effect?

In this session, you will take the results of your initial inquiry activities and research analysis from the first two sessions and produce a piece of accessible research writing.

Now that you know how to ask a research question, conduct research, and analyze your findings such that you can make a storyboard or outline, it’s time to finish drafting your presentation, report, or essay.

While many writers compose narratives chronologically, research writers tend to compose their texts in chunks. They might write a short introduction to frame the main idea of their report or presentation, but then move to the center of the report or presentation to work on a key idea. By using a storyboard or outline, you can easily move around in your report or essay to different sections and not lose the overall coherence of your work. This nonlinear composing process also helps with fatigue when working with complex research.

Getting feedback on your inquiry-based writing: Inquiry-based writing can be as emotionally felt as healing narratives. For that reason, you might want to revisit the advice on intensity of response from Module 1.

While inquiry-based writing can take many forms, there are some key elements in all research writing. So, while you may or may not have a friend who can evaluate the technical content of your inquiry-based writing, you can still have a friend give you some feedback on the following:

What is the research question?

Why is that an interesting research question? If you can’t tell, offer some suggestions.

What data did the writer collect to answer that question(s)?

Do you feel that the writer has enough data to answer their research question? Why or why not? Do you feel that the researcher has the right kind of data to answer their research question? Why or why not?

What is the biggest surprise in the findings? What seems to be the most important finding?

What remains unclear to you after reading the draft?

“The literal meaning of advocacy is ‘mouthpiece.’ So I think of advocacy as using my voice to help people find theirs. This has involved public speaking, writing, teaching writing, and guiding performances. But it’s primarily meant being present with someone: carrying a piece of “it”, whatever “it” is for her or him. A memory, crisis, trauma, an achievement, a milestone… Advocacy requires trust, suspended judgment, and partnership. I listen to stories, and I reciprocate by sharing mine. There’s no room for “experts”—it’s a co-navigating of life’s difficulties and redemptions.”

—Christy Birch, interviewed for Ploughshares by Tasha Golden in “Where Your Writing Can Go: Storytelling as Advocacy”

(CW: sexual violence)

Now that you have a firm grounding in your self-generated research projects, the community entry point activities that follow in this module help you position yourselves within larger community responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Community-based prompts are for writers who want to advocate for a particular position and work with members of their own communities. These activities also provide a foundation for the skills, such as interviewing.

In this module, we offer participants two ways of using writing for community-based projects: op-eds and oral histories. Op-ed advice is targeted for participants who want to take their self-generated research inquiries and use their findings as means to advocate for particular positions, interventions, or recommendations. Oral history advice is for participants who want a more intimate way of using writing to advocate for community awareness by capturing the stories of community members. Activities in this module guide writers through the writing process for both of these activities. This module follows three steps:

Identify common types of community-based writing.

Generate op-ed pitches and trauma-informed interview questions to support public-facing narratives and oral histories.

Draft an op-ed or transcribe an oral history interview.

Community-based writing values the perspectives of individuals outside the academy. That means, community members’ ideas guide the research and final product. For example, op-eds are often meant to give voice to individuals who are not professional journalists but who may have particular expertise in a topic or lived experiences that offer readers valuable perspectives. Other community-based writing projects, such as oral history projects, are meant to document people in specific locations at specific times in history.

Op-Eds

Provide a non-journalistic perspective on a current event

Include opinion and research to support claims

Offer readers awareness of an issue, a solution to a problem, or a call to action

Oral Histories

Value the perspectives and words of community members

Capture individual opinions and experiences

Can be used for historical and/or educational purposes

Not the same as therapy

In this session, you will gain exposure to these common types of community-based writing, including strategies for developing your ideas as well as reading published examples.

Published Op-Ed models:

Reann Gibson, “Communities of Color Hit Hardest by Heat Waves”

David Lat, “People Ask Me If I’ve Recovered From Covid-19. That’s Not an Easy Question to Answer”

Sabrina Strings, “It’s Not Obesity. It’s Slavery”

Op-Ed resources:

Indivisble’s Writing Op-Eds That Make a Difference

Kristine Maloney, “Op-Ed Writing Tips to Consider During the Covid-19 Pandemic”

The Op-Ed Project’s Op-Ed Writing Tips and Tricks

Published oral history models:

Journal of the Plague Year’s Covid-19 Oral History Project

Columbia University, NYC Covid-19 Oral History, Narrative and Memory Archive

Trauma-informed interviewing resources:

Jo Healey, “Reporting on Coronavirus: Handling Sensitive Remote Interviews”

Jina Moore, Covering Trauma: A Training Guide

Jina Moore, “Five Ideas on Meaningful Consent in Trauma Journalism”

Katherine Porterfield, Trauma-Informed Interviewing: Techniques from a Clinician’s Toolkit (video)

Aras et al. Documenting and Interpreting Conflict through Oral History: A WORKING GUIDE

Columbia University, Resources for Covid-19 Interviewing

In this session, you will apply the strategies from the previous section to your own writing process, clarifying your stance and audience through drafting a pitch for op-ed projects and generating interview questions for oral histories and similar narrative projects.

Use the following questions to help draft your brief pitch and begin framing your draft:

Why write an op-ed? Clarify your purpose:

Inform (make aware of)

Educate (going a little deeper)

Persuade

Inspire

Advocate/offer call to action

Relate

Basic questions to draft a pitch:

What’s your issue? What is the “hook” or current event that frames this piece?

Why right now?

What’s your unique perspective/recommendation within this issue? What is the counter view to this?

Why should you be the one to write it? (credentials, relevant life experiences, etc.)

Where should you pitch it? (local or national publication)

The argument: How are you making your case?

Anecdotal evidence—the personal, contextual details that engage the reader (potentially from Module 1)

Research—the evidence to support your recommendation or position (from Module 2)

Testimony—the words of others to help you make your case (from oral histories)

The writing:

Be as concise as possible (typically around 750 words)

Use active voice

Avoid clichés

Use specific examples

Have a consistent voice

Know your audience

What are the goals and purpose for collecting these oral histories?

“To provide a historic record of what has happened and its multiple impact on individuals and within communities.

To share the results of these findings with professionals who make humanitarian interventions in the aftermath, and to record the success and failures of those programs if resources permit.

To support those who give testimony in creating narratives that through their very expressivity and creativity can help rebuild communities and reconstruct identity in the wake of the catastrophe.” (Albarelli et al., 2020, p. 13)

Define the frame of the project:

Place. Currently, most interviews should be conducted remotely.

Time. You must decide if you will interview someone while an event is happening, immediately after an event, or after some period of time has passed since the event.

People. The people you interview are called “narrators.”

Technology. Decide what technology you will use to conduct the interview.

Legal issues. Read the claim rights, if you are using professional software for interviewing.

Select the focus of the interviews:

Will you focus on a specific moment in time or an expanse of time?

Will you use the same questions for each narrator, same themes but varied questions, or freeform format?

How long will you interview a narrator?

Will you be seeking a second interview?

Will you give narrators the opportunity to listen to their interviews?

Develop a plan for listening and publishing interviews

How will you listen for accuracy of meaning?

How will you address awkward passages or inaudible passages in the interviews? Will you remove filler words like “uh” and “um” from the transcripts?

Will you trace themes across interviews and provide an analysis or build compelling profiles of individual narrators?