.

Abstract: This assignment encourages active, holistic analysis and articulation of the distinctive features of an artist’s body of work. In preparation for a final essay interrogating a pattern across multiple works, first-year undergraduates at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts create a style parody of, or homage to, their chosen artist’s work in a medium of their choice (which may or may not align with the artist’s). After studying the artist’s patterns of form and content, students gain a deeper perspective on those patterns by actively distilling them into a work that reflects and/or exaggerates what they’ve observed. The assignment engages creative and metacognitive processes, including thinking from the perspective of the artist, and gives them a tangible reference point to both consider and move beyond in their upcoming essay.

In the classic Saturday Night Live sketch “James Brown’s Celebrity Hot Tub Party,” Eddie Murphy channels a typical James Brown performance, including his over-the-top, enthusiastically heralded entrance, raspy, percussive vocals, tightly-coiled dancing, affirmative call-and-response, guttural interjections, and his signature “Cape Act,” in which Brown feigns exhaustion, prompting backup singers to drape him in a glittery boxer’s cape and lead him partly offstage, only to abruptly shed the cape and bounce right back, stronger than ever. At least half the lyrics are variations on the words “hot tub,” and the snaky, horn-driven groove evokes Brown’s “Cold Sweat” without getting too close to mimicry (Saturday Night Live 2019). My students watch this at the end of a class in which they’ve heard an expedited introduction to about a dozen JB tracks, and collaboratively answered the question, “If you had to explain to a band who had never heard James Brown how to sound or perform like James Brown, what would you suggest?” (No musical jargon needed.) The “Celebrity Hot Tub Party” capstone ties many of their observations together in a concentrated form, and from their laughter, I can tell that they instantly recognize Brown-esque tropes even if they hadn’t explicitly named them.

In the second semester of my “Writing the Essay: The World Through Art,” NYU’s core writing course for students in the Tisch School of the Arts, the first major essay asks students to create an argument about an artist’s body of work. Although the essay requires research into motive, context, and discourse, the central argument must be built around the student’s own observations and interpretations across multiple works; in other words, they need to identify and focus on some kind of iterative pattern (NYU Expository Writing Program, n.d.). To achieve this, students need to develop their own sense of what the artist’s work is “like”: not just with respect to formal details but also subject matter, perspective, style, tone, and other holistic qualities. Their first assignment asks them to extract “meta-narratives” (specific commentary about certain ideas or issues that echo across plotlines) from any three episodes of the anthology TV series Black Mirror, which gives them a chance to work from a common reference point and notice how different formal readings can emerge from the same body of work, as well as how these readings depend on the works one chooses to examine. From there, they propose an artist to work with and make preliminary observations about patterns of form and content that they notice.

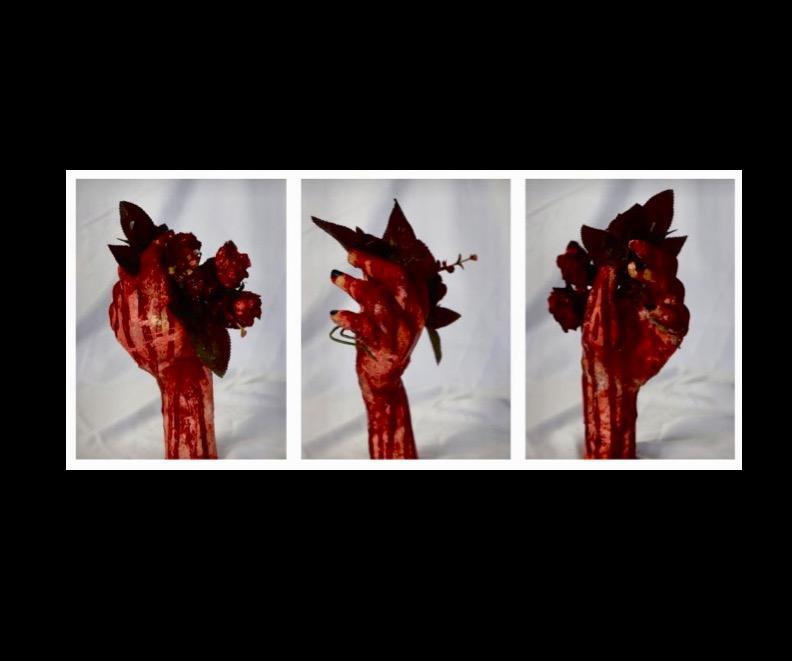

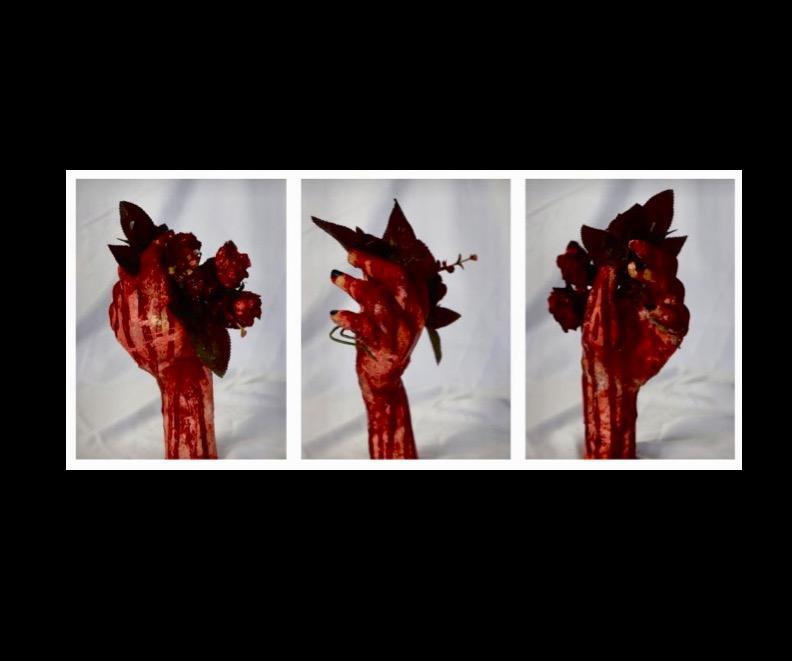

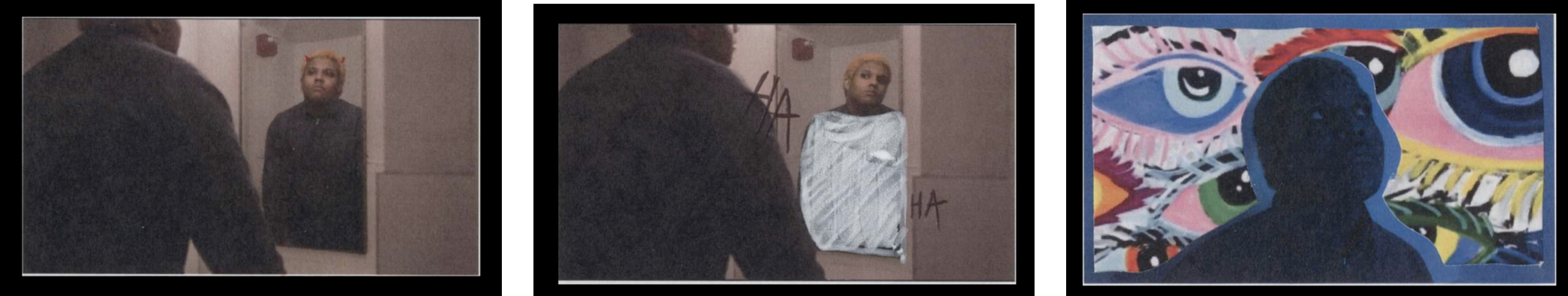

Many students have difficulty getting beyond the obvious, best-known, or most-talked-about characterizations of the artist’s body of work. Prior to creating this assignment, as students began drafting, I had noticed a gravitational pull towards “proving” what’s clearly there, or at least widely assumed or discussed, even when encouraged to look more closely. To promote more active, close observation before drafting begins, I now ask students to creatively evoke the distinctive features of an artist’s work--rather than simply naming them--in an assignment I call the Homage/Parody Project. The goal here is to make a game of actively recognizing how the artist’s work is perceived, so that they have a point of reference to write beyond in their own argument. To put it another way, they create a caricature of the artist’s work-–this could be in the form of a photograph, a song, a short film, a sculpture, or even fashion designs--ahead of time so that their essay can do more than that (see Figures 1 and 2). In some cases, while creating the parody or homage, students also stumble upon less obvious, more insightful patterns that can serve as a foundation for their essay.

We focus on two characters on their way to the gallows.

PATTY ...Quite a nice courtyard, innit?

CONAN: Oh, yeah. Fine architecture. A real stunner.

PATTY: Aye... And a beautiful day too.

CONAN: Aye that, Patty.

PATTY ...Say. Coney. You ever think we’d be hanged on a day as nice as this one?

CONAN: Not a chance, Patty, not a chance.

(Excerpt from a student parody of Martin McDonagh’s screenplays [Student Parody/Homage Project, 2024])

The project was partly inspired by Samuel Hubbard Scudder’s 1874 essay “In the Laboratory with Agassiz,” alternatively titled “Take This Fish and Look at It” (a popular reading assignment across academic fields, notwithstanding some of the deeply wrong lessons Agassiz taught in other contexts) (Scudder 1874). In it, Scudder describes his education in natural history, which began with a simple prompt from his mentor: “Take this fish… and look at it; we call it a haemulon; by and by I will ask what you have seen" (p. 217). What Scudder assumed would be a ten-minute exercise turned into hours and days trapped alone with the small specimen, under orders to relentlessly document its features along every observable dimension. After hours of staring at the fish with little to show for it, Scudder recalls: “At last a happy thought struck me - I would draw the fish; and now, with surprise, I began to discover new features in the creature” (p. 219). In other words, after a piece of evidence seems to be exhausted of analysis, new observations and insights may come through acts of creativity: we don’t just draw what we see, we see what we draw. Creating a parody or homage can lead to a more complex and integrative version of this experience.

.

As with Scudder, the road to the parody/homage (and from there, to the essay) starts with intensive close observation. From the first class of the semester, my students practice a focused, persistent commitment to seeing (or, as applicable, hearing, smelling, touching) a work, well beyond their instincts to declare the task “finished.” Working from both Jean-Honore Fragonard’s (1767) painting The Swing and Yinka Shonibare’s (2001) re-interpretative installation The Swing (After Fragonard), students are given several minutes to note as many direct observations as possible about either work, or their relationship to one another. At the end of this time, which they expect to be the end of the activity, they’re given another several minutes and challenged to make at least as many additional observations, and then this repeats once more, with suggestions about how they might observe from different perspectives. Next, students merge their observations with a neighbor’s, and then together they take one more crack at finding more previously-unobserved attributes. Finally, for the first time, students are given random bits of historical and aesthetic context (drawn from an envelope) and asked to reflect on their observations in light of this new evidence.

Like many of my classroom activities, the “writing” part of this process is limited to jotted notes, not complete sentences or paragraphs. This is by design: I believe that an obstacle to strong student writing is writing too soon, without taking sufficient time to observe, think, puzzle out, and even play. This echoes Peter Elbow’s emphasis on judgment-free, unconstrained "freewriting" as a necessary step toward insightful finished work (Elbow 1998, p. 3–9). In my experience, as soon as they begin even a rough draft, their attention shifts to sentence structure, word choice, grammar, syntax, and other writing mechanics, which can trigger anxiety and indecision in some students and myopic over-confidence in others. Without a strong bank of at least partly-formed, semi-developed ideas, an early draft might make only minimal progress toward a fully developed essay.

The Homage/Parody Project itself, assigned shortly before the first draft, re-imagines and elaborates on Scudder’s fish-drawing exercise: rather than re-create a specific work, students are asked to consider multiple works in order to create a new one in the same tradition. From “Celebrity Hot Tub Party,” they learn that parody is a play on form, compressing and heightening recognizable traits, perhaps in a humorously incongruous context. For students who would rather treat their artist’s work with more reverence, or simply would rather not “try to be funny,” I offer the option of an homage, which I illustrate with British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare’s (2013) Self-Portrait (After Warhol). That said, I assure them that irreverence is not the same as disrespect, and that many past projects meant to be homages actually work as parody, while some intended parodies actually become very successful homages. The goal in either case is to integrate their observations into a holistic impression, and to reflect that impression back in a new work.

The educational value of parody has been recognized before, at least as far back as 1939, when The English Journal published “The Use of Parody in Teaching” by young Massachusetts high school teacher Earl J. Dias. Feeling stymied by his class’ difficulty interpreting Joseph Conrad’s work, Dias turned to parody, reasoning that

A good parody is like a telescope. It can magnify the characteristic of a writer's style to such portions that even those comparatively inexperienced in the tenets of literary criticism may be able to achieve at least a partial understanding of the peculiar qualities of the type of writing that is parodied. (Dias 1939, p. 650)

He turned to Max Beerbohm’s collection of parodic essays, A Christmas Garland, one of which “manage[d] to convey perfectly the little idiosyncrasies that make Conrad's writing instantly recognizable to his more avid readers.” Dias’ students not only were entertained, but also were subsequently “able to discuss with improved understanding the typically Conradian characteristics” (Dias 1939, p. 651).

Although Dias didn’t ask his students to write parodies themselves, he does suggest to the reader that “more talented members of the class may also be tempted to try their hand at parodies. This is to be encouraged” (Dias 1939, 655). William J. Bintz (2012) describes a lesson that does just that in “Using Parody to Read and Write Original Poetry.” His graduate students (mostly teachers themselves) were challenged to parody classic poems to make new statements; results included commentaries on consumerism (“She Walks in Gucci,” to Lord Byron’s “She Walks in Beauty”) and plagiarism (“Stealing Others’ Work Is a Form of Cheating,” to Robert Frost’s “Stopping By the Woods on a Snowy Evening”) (p. 74-75). In student reflections on the activity, Bintz noted several forms of “active engagement” (p. 78). Some, like the author of the Frost parody, cited careful attendance to distinctive formal details:

To make the parody apparent, I thought about what the most distinctive features of Frost's poem are and tried to duplicate them. These included the length of the title, the famous first line, and the repeated final line. I was able to maintain the AABA rhyme scheme and eight-syllable lines of four iambs as well. (p. 76)

In my own class, students have described many forms of “active engagement” to better understand and conceptualize their chosen artist’s work and craft. For example, a student who made a short film in the style of Andrei Tarkovsky had to come up with a creative workaround to mimic Tarkovsky’s camera work without sophisticated equipment:

[An] element that Tarkovsky utilizes a lot in his films to create tensions is a “push in”. This is where the camera is pushed into a specific object in the frame. However, this requires a dolly or gimbal to shoot it smoothly, which I do not have access to. Therefore, I created the same effect with a digital zoom in post production…

In his film Stalker, Tarkovksy juggles between a blueish film stock and sepia film, which has a very bronze color to it. Since I didn’t have access to the film that Tarkovksy used, I decided to replicate his look with color grading. Some of the shots have a blueish/grayish tint to them, and another has a bronze tint to replicate the sepia film. (Student Parody/Homage commentary1, 2024)

What this student (and so many others) reminds us is that the creative act of this assignment doesn’t just help students notice new things about an artist/evidence--they also gain understanding of something they’d already noticed. Relatedly, parody has, built into it, the acknowledgement that you can’t be "as good" as the original--even Eddie Murphy, a good singer, can’t match James Brown--but in problem-solving around the limitations of time, resources, and their own skill set, students make discoveries about how an artist works in a medium.

To expand their creative problem-solving opportunities, students are not required to create a work in the artist’s preferred medium. Many do, of course, but this allows students to choose artists beyond their own field, and for students in an arts program, choosing a medium that they’re not “supposed” to be good at can be creatively liberating. Crossing modalities can also lead to interesting metacognitive work, as with this student, who designed a cardigan sweater inspired by the Belgian singer and rapper Stromae:

This cardigan is inspired by Stromae’s style and his fashion label, mosaert. In an interview with Pitchfork, he revealed that for every song on his second album racine carrée, there was a specific look…For example, the music video of “Tous les mêmes” ends with the camera zooming out from a house to the entire neighbourhood into a pattern of hearts. For my design, I used circles as the pattern, and pink as the main colour in reference to his revamped trademark bowtie he wore while performing on his last tour. If you look closer, you can see that the circles are actually made up of pictures of washing machines—my representation of the recurring cyclic themes present in Stromae’s songs. In “Alors on danse,” one dances to forget their problems, but they’re still there at the end of the day. In my pattern, one puts their dirty clothes into the washing machine and they come out clean, but inevitably, they will get dirty again. (Student Parody/Homage commentary, 2024)

In my course feedback, students often cite the Homage/Parody Project as among the most useful of the entire semester because it helped them “dive into the essence of the artist in a way that was extensive but felt fun”; another student noted it “allowed me to understand different traits” of their selected artist. A third student, echoing the analytic power of the creative assignment, also wrote that they “felt closer to [their] artist”.

Another reason I keep bringing this project back is the consistent strength of the student work. More than in any other minor or major assignment, students tend to put a good deal of effort into these projects - in some cases, arguably much more than necessary! They seem very motivated to impress their peers, and greatly enjoy seeing one another’s work. The projects that turn out less well than the others often simply reflect a lack of time and effort. Some students also fail to grasp the difference between homage and near-copying - an admittedly blurry line in some cases. Often, this comes from focusing too much on a single work by the artist rather than integrating multiple works into a new one. For this reason, it’s important to emphasize the holistic, broadly imitative nature of an homage, as well as the difference between direct and style parody. In a few other cases, seemingly ironically, the parodies fall flat because the students don’t quite take them seriously enough. They might see it as an opportunity to be merely ridiculous instead of thoughtfully ridiculous. When showing models, such as “Celebrity Hot Tub Party,” it’s crucial to point out the level of detailed thought and craft behind even a goofy sketch.

The Homage/ Parody Project may even have broader benefits in shaping students’ worldview in the face of misinformation. In our current epistemological climate, in which everything from homework to world news is increasingly easy to fake, University of Edinburgh digital education expert Christine Sinclair (2019) argues that “parody is important because it is used not only to generate fake news but also as an antidote to it” because “for parody to work, it needs to be distinguishable from fake news, and for the author and the audience both to be in on the joke” (p. 61). Through multiple examples, from parody news headlines to discourse about Brexit, she suggests that understanding parody can help students understand how real information is exaggerated, distorted, and manipulated, and how this differs when the purpose is humorous commentary or malicious deception—important skills in a world in which reality and parody are increasingly difficult to tell apart.

For this project, you’ll draw on your evolving understanding of your artist’s body of work to create a miniature riff on it, in the form of an homage or a style parody. The more of your artist’s work you’ve encountered, the better you’ll be able to do this.

The general definition of “homage” (silent h) is “something that is said or done to show respect for someone” (Oxford English Dictionary). In the arts, it’s used to describe a work that alludes to, or imitates, another artist’s style or another specific work, without crossing into outright plagiarism. For example, the TV show Stranger Things is, in part, an homage to sci-fi and paranormal films of the late ‘70s and early ’80s, including Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Gremlins, E.T., Poltergeist, etc. The Season 1 Stranger Things poster bears a deliberate resemblance to a famous original Star Wars poster. (For a video montage of more Stranger Things homage moments, click here.)

Parody is a more familiar concept. As we noted in Eddie Murphy’s “James Brown’s Celebrity Hot Tub Party,” it’s primarily a play on form. The form of a particular work or artistic style is compressed, heightened, and/or grafted onto arbitrary or incongruous subject matter for a comic effect. “Celebrity Hot Tub Party” is an example of a style parody--it mimics the effect of a James Brown song and performance in a holistic sense--as opposed to what one might call “direct parody,” like goofy lyrics set to the tune of Brown’s “I Feel Good”, or a skit in which Marvel’s Avengers try to manage a Burger King. If you choose to do a parody, you’ll be going for a style parody of the artist’s body of work, not a direct parody of one particular work.

The line between homage and parody is blurry. Often, the funniest parodies show an underlying respect for and understanding of its subject; conversely, homages are often at least somewhat funny if the style is immediately recognizable. You might set out to make an homage and actually make a parody, or vice versa. If that’s what happens, that’s totally fine! Choose whichever approach (homage or parody) feels more helpful to you from a creative standpoint, and let the product become what it is.

Here’s what you’re being asked to do: Get into the mindset of your artist and make an homage or style parody of their work. You have a lot of leeway in how you do it. The most obvious example is to create your own “work” by the artist that doesn’t actually exist. But you’re also not limited to the artist’s original medium. For example, you could make a photographic montage in homage to a choreographer, sketch out a set design for an imaginary new play by a playwright, show us what a country & western song written by a particular filmmaker might sound like, etc.

You may present your exhibit as a stand-alone piece, or as an “excerpt” from an imaginary larger work. (If you choose the latter, you don’t need to explain or map out the larger work in detail; just acknowledge what it is.)

Some types of exhibits you might submit for this project:

A one-minute film, or one-minute trailer for, or “excerpt” from, an imaginary new film/TV show by the artist

A photograph, or series of up to 5 photographs (more isn’t necessarily better; it depends on what you’re trying to put across)

A drawing, painting, or sculpture

A 2–3-page written scene in screenplay, teleplay, or stage play format

A one-minute recorded song or song “excerpt”

A one-minute monologue (as a script, and/or performed on video)

A one-minute dance sequence (on video)

A one-minute “pitch” for a new video game (accompanied by some sample artwork and/or simple animation)

A simple interactive online experience

Anything else you’re inspired to make!

Along with your homage/style parody exhibit, you must submit a short

commentary (at least 200 words) explaining the choices you made in

creating your homage/parody exhibit, and how those choices reflect your

artist’s work and interests.

Goals for this assignment:

To articulate typical, prominent, or distinctive elements of form and/or content that characterize your artist’s body of work.

To think about your artist’s body of work in a new way by attempting to create something that resembles it.

To create your own reference point for your artist’s body of work that you can continue to expand, develop, and complicate as you draft your essay.

To do something hopefully a little bit fun for credit.

A successful project will creatively capture or allude to multiple elements of the artist’s work, and clearly explain/contextualize the allusions in the commentary (which should be written for someone who isn’t familiar with the artist’s work).

Again, you should not parody just a single work by the artist –try to reflect their body of work as a whole. Similarly, avoid collage/copy and paste jobs that just string literal bits of specific works together. You may, however, include elements that playfully suggest specific works, and/or evoke quintessential images/motifs/themes/tropes found across their body of work (like Yinka Shonibare’s Dutch wax fabrics and headless mannequins, for example).

Both the project and the commentary should be uploaded in a format that’s readable or playable by most computers. We will share some of these in class!

Deliverables: Your very own homemade parody or homage exhibit (see various suggestions above, feel free to email with questions) plus a 200-word commentary (doc, pdf, etc).

In a sense, the commentary requires the student not only to articulate their own thinking directly, but also to summarize that thinking from a position of removal. This parallels John C. Bean’s (1986) embrace of summary writing, in which a student must "temporarily abandon his or her own perspective" (p. 344) in order to "articulate ideas different from their own," but here, the homage or parody itself "summarizes" the artist's work through artistic interpretation, not a direct summary, and in turn, the commentary asks the students to comment on and interpret their own thought process that led to that interpretation.↩︎