Abstract: Historically, in NYU's Expository Writing Program, we tend to use a pre-selected array of texts as a basis for major essay assignments, to allow students a variety of choices of style and subject matter to engage while maintaining control over the selection. Here I show how using one rich text as the foundation in a major first-semester-writing assignment is useful and interesting for teaching reading and maintaining an overall sense of cohesion and centeredness to the course, and I also demonstrate my process of asking about and exploring this particular practice. My own writing process for this piece—inductive and recursive—mirrors the process I have scaffolded for my students; my own essay—driven by idea more than thesis, structured in conversation with my idea—also mirrors the kinds of prose I encourage my students to craft. It is my hope that the culmination of the following progressive sections shows possibilities for using one foundational, rich text to teach a classroom of students to write an essay that is truly driven by inquiry rather than thesis, one that highlights the process of discovering and creating ideas and thrives in doubt.

I considered the idea of teaching with one anchoring text for a while before I actually did it. It seemed like a tough pivot from the Expository Writing Program’s “handful of texts” approach. Again and again, my faculty agreed that students should have a variety of assigned essays to choose from. Giving options allowed for them to feel they were reading something they liked instead of having a specific theme or short story or essay or book forced on them, especially in a class they’d been required to take. This would get them more engaged, make them write a better essay, our logic went.

On one hand the assignments we give at EWP are meant to be capacious and generative, but they also have very particular parameters; a foundational parameter that has persisted until today is reading together three to four essays for students to pick from for their primary source text, which they go on to examine in our research assignment with the goal of asking questions that both take the writer beyond that text and allow them to return to it and see it anew, showing this shifting understanding and its greater significance to their reader. In the past, these source essays were limited to our assigned course reader and tended to be belletristic, personal (some deeply so), and expansive in their ideas. But, over the course of the last decade, we’ve shifted what’s permissible to assign. Still, we’ve continued sharing groups of essays with our students at once, as the beginning of a progression of exercises. (In EWP, “progression” is used to refer to the sequence of assignments that begins with close reading and leads up to a final graded essay.)

Teaching an array of texts and having students work in this way in my own classroom has gone well but also it has been a strain in terms of how our collective energy as a class is spent, especially when conversing about readings, and grappling with particular themes and ideas.1 And so I continued to fantasize about teaching just one common written text as the basis for the largest writing assignment in the course. This assignment asks students to consider and reconsider specific concepts and references from a central text, and select ancillary texts to put into context with that primary text. The challenge is to create a conversation between texts that nonetheless moves toward the student’s own idea; the challenge is to do a lot of reading and researching but then structure and order that reading process into a written essay. And so I kept asking: was there a single text we might originate our progression’s work in that contained many possible paths of further explorations for students to take on, which would lead them to many possible connections to outside texts, connections they might then take ownership for when they led to other research and original claims and then ultimately their own ideas? Was there a text rich enough and approachable enough to appeal in some way to all of us?

“I’m anxious about speaking in front of the class too,” I tell my students, “even after over a decade of being a teacher here.” They look at me, incredulous.

They are floating on the high of just having turned in their first essay after a month in this room together, and I’m trying to get them interested in the next thing.

I tell them I’m just like them, but I have a little more experience, some tricks up my sleeve. We are going back to the skill of reading, and we are focusing on reading one big essay together for a while. “It’ll be fun,” I shrug.

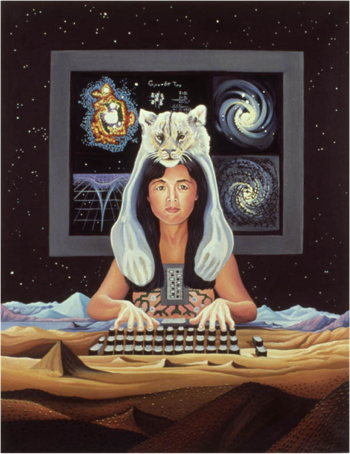

Up on the screen in front of us, I project an image that I’ve used in front of classes just like this for a handful of semesters now, asking if any of them have seen it before. They shake their heads (Figure 1).

One thing I know for sure is that using a visual image to open a writing class is quite often successful in engaging the group. Much scholarship has explored the benefits of using visual images and other multimodal works to mediate the learning of writing, including Fleckenstein (2004). Most interesting to me as someone who has spent a majority of classroom hours working with international students is understanding how this is an especially beneficial approach with English Language Learners (Lee, Lo, and Chin 2021). So, as I did on the first day of this class and several times since, in classes both meant for fluent and non-fluent students, I begin by writing my observation questions up on the board and referencing Figure 1:

What do you see? (Minute Particulars)

How does it work? (Form)

These prompts are simple and addressing them slows down the process of looking, turning it into a group activity of generating language together. I write their observations up on the board, or, better yet, ask for two volunteers to write them. I tell them they should be writing them down in their notebooks too.

“A woman,” one student says, calling out.

“Really?” I say. “What makes you think that?”

“Oh,” the student says, “right,” scratching their brow, squinting, as if gender works like that. And they might indicate the figure in the digital image’s long hair, their facial structure, acknowledging now that it only might be a woman.

“Ok,” I say, noting I am glad to see we are learning to be honest about what we observe, to allow doubt in what we first assumed. “What else?” By this point in the semester, they know each other well enough to feel somewhat comfortable. And they know I expect them to be genuinely curious, to contribute. “Come on,” I say. “Name the minute particulars!”

Each student takes a turn, and some go multiple times.

There are so many things in this image to point to: the white wildcat with skeleton showing through its skin that the seated humanoid figure wears as a headdress, the computer chip breastplate they wear, which serves as the canvas’s center, the white (snowy?) terrain behind them, the keyboard they are using that is set up on a desert terrain that stretches across the foreground. And behind the figure is a curious mosaic of images, featuring a blackhole, a galaxy, what looks like a heat map of a cell, some sort of a mathematic equation. All this set against a vastly starry sky.

It's not particularly complex or beautiful, rather like a childish sketch with a simple palette of paints taken to it, and yet the various symbolic elements, and the being’s placement in the middle, is larger than life—"like they are programming the universe” a student of mine once said. They share other notions, about the bringing together of opposites, the bridging of the binaries posed in their observations of the being’s gender, in the combination of warm and cool colors, in the juxtapositions of space and earth, nature and technology, future and past.

This image provides a wealth of details that I find as a powerful tool for moving towards meaning-making, gesturing at the thing they will practice again and again, in the smaller stakes exercises and prompts that lead them to writing their research essay. Ultimately, they will lay out evidence that they have observed carefully, making meaning of it by creating a structure that leaves and returns to a central piece of evidence; they'll have to change what a detail reveals by framing it and reframing it in connection to sources; they'll have to construct an order of meanings, a provisional interpretation which they then complicate and layer in ways that both surprise and satisfy the reader. But they will only be able to do that successfully after they’ve practiced asking our observations questions again and again. “What makes you think that? What do you see?"

“Minute particular” is a term I first remember hearing from Pat C. Hoy II, in Fall 2013, the beginning of his last year as the head of the Expository Writing Program, and my first as a teacher there. He’d begin our training sessions for first-year teachers and workshops for the full faculty by presenting images, or music, or film clips. In a sort of mysterious way, he’d ask us to point out what we noticed in them: “Just to start there, with the minute particulars—it’s just what it says, the tiny, specific things. Easy, right?” A lesson on more than whatever we were looking at, a lesson in teaching, I’ve used it in my own classroom every semester since. And the truth is I’d always just taught and assumed it meant what it said: small, specific thing.

Only now, eleven years in the future, do I type “minute particular” into a search bar and realize it’s a concept that comes from the great British poet William Blake, a line from his poem, Jerusalem: “He who would do good to another must do it in Minute Particulars / General Good is the plea of the scoundrel, hypocrite, and flatterer / For Art and Science cannot exist but in minutely organized Particulars” (Blake 2014, p. 752). Beyond specificity, Blake’s lines show me that the minute particular seems to impart some special relationship between part and whole, some quality we can think of as true, “good” to the person who observes it, witnesses it, chooses it, takes the time to write about and explain it for an audience of readers.

These notions about teaching writing only come out of writing these very paragraphs. My own writing process—of minute particular to question to observation of an outside source to new understanding about the detail and larger meaning connected to it, written out and shared with a reader—adds to my approach in teaching my students. Note that it took me years to even begin, in this instance. And so it is by some sort of blind faith that we teach the practice semester by semester, moment by moment, more than simply by explaining it, but by shepherding our students through many chances to do it—with visual texts, written texts, aural texts, objects, working both together and alone—and by doing it ourselves, again and again.

In addition to direct observation and true reading comprehension - what Robert Scholes (2002) calls “to grasp and evaluate” (p. 171), at EWP we seek to add layers to our students’ understanding of how the written and visual texts we are reading and otherwise looking at work on us, as viewers, as readers. We seek to create a vocabulary around form, and, in recent years, many of us have sought to enrich the ways we talk about the related notion of context.

“Context”—I look the word up with my students every semester, thrilled to share the etymology with them: it’s Latin for “weave together.” So, it is anything beyond the minute particulars, the layer around them, the web between them.

Again, I go back to my “questions of observation”: “And how does it work?” I ask, pointing at the glowing figure who looks like some kind of Indigeno-futurist queen, indicating my second question: “What is it?” “What’s it doing?” This one is a little harder to get to, harder to find words for. But we persist. We agree the thing itself is a painting presented here in this room in pixels, and that the mixture of elements—the centeredness, the mirrored juxtapositions—give a sense of a very powerful person, who straddles worlds: the natural and the technological, masculine and feminine, inner and outer.

Then, I share basic background—“another layer of context,” I emphasize to them. Lynn Randolph painted the piece in 1989, while working in collaboration with Donna Haraway (Randolph 1989). She called it Cyborg. I explain we will be reading Haraway’s seminal work, “A Cyborg Manifesto”, which was an essay first published in 1981 (Haraway 2016). The painting came well after the essay, though it feels like they might have been created simultaneously, as if they were made in some true version of our many possible futures.

Not quite long enough to be a book in its own right, but much longer than anything we have read in my class up until now, Haraway’s long essay is a mishmash of words and ideas, rife with concepts that, if given readerly care and attention, weave a luxurious and fascinating web between feminism and technology and nature that shows a future-oriented world of hybridism and possibility. And all this playfully, pragmatically set against a political context Haraway warns us will take every possible advantage over all of us, particularly if we let obvious and dangerous binaries control our lives. Haraway posits the metaphorical image of a cyborg princess (perhaps something like she that Randolph depicts) as the hero/ine that can rise in such a context.

Too early to bring any of this up too. As teachers we have to remind ourselves and our students to hang back, to make the space to pay attention.

After we adequately investigate the image of our cyborg would-be goddess, I project my step-by-step library search up for “A Cyborg Manifesto” on the class’s main screen, noting that it is the focus of a larger book—Manifestly Haraway (Haraway 2016), which also includes an introduction by Cary Wolfe, a scholar of post-humanism, and a follow-up by Haraway that adds considerations of non-human species to her arguments, a direction she continues to take in current scholarship. We marvel at all this context, and then I ask my students to close their laptops, as I hand out a printout to each one.

Besides the thunk of an 80-page document on their desks, there is the sublimity of reading on real paper and with a pen in your hand something written in the past but about now, and also about the future.2

As inevitably my students begin to flip through the pages, I ask them to skim mindfully, to tell us about the section headings, as well as the charts they see. We talk about the endnotes and bibliography together—both of which are extensive. What does what you see tell you? I ask. The writer has a lot of different ideas and sources she’s taking from. She wants to make sure we know she’s done her research. I might say something about research lineage, maybe write that concept up on the whiteboard, and they flip through the pages.

With the thing itself in front of us, they cannot rely on the Ctrl-F function, cannot quickly copy-paste the whole thing into a summarizer. Sure, some will do these things on their own, later on, but at least for now, there is only the thing itself, the words on the page in front of us.

Next, I set the class to skimming, looking for “compound concepts”3, which are the minute particulars we are on the look-out for in this observation. I describe them on a slide as follows: “Concepts are nouns that we use to define abstract ideas we cannot place in the physical world. Concepts include things like: ‘artifice’, ‘femininity’, ‘science’, ‘knowledge’, and ‘apocalypse’. And compound concepts manifest when more than one concept is put together, creating a concept that is more specific, or specialized. You might make a compound concept by combining a concept with an adjective that also speaks to a concept (‘abnormal science’), or by connecting concepts with ‘of’ (‘folly of belief’), or by adding a concrete word to a concept (‘cell phone knowledge’).”4

Most texts will have two or three compound concepts that seem to unlock the rich font of the essay’s meaning, but Haraway, in particular, has a dizzying amount. As we begin looking, students immediately see:

ironic political myth

rhetorical strategy

political method

world-changing fiction

international women’s movements

And this is just in the first two pages. We take time to carefully define at least one of these compound concepts together, based on what we see in the text, then what we already know, then we look them up online—using a regular search, then the Oxford Dictionary, then NYU’s library databases to get us to the reference database Credo. Students then crowdsource a number of these compound concepts on a shared document, and their first short writing assignment in this progression comes after this lesson; each student is tasked with choosing a compound concept most intriguing to them and representing both the moment in Haraway’s essay where they encountered their compound concept, followed by the sources they used to investigate it, culminating with their own understanding of it and further questions this new knowledge raises about Haraway’s text and the world beyond it. Although they often ask if they can simply write out bullet points, generally I ask students to complete this writing exercise and all that follow in full sentences and whole paragraphs with the aim of explaining them to someone in another class like ours who is not reading Haraway’s text.

This becomes each student’s first unique doorway into their own writing work, an initial opportunity for observation and research. Through this writing comes a chance to consider the kinds of choices they want to make–about questions they will ask of the text, about sources of their own choosing they want to spend time with. This practice of observe/ask/investigate/write continues throughout the progression, a cycle that grows more complex with each repetition, as they move through drafting and research again and again before they get to turn in a final essay.

Over the following weeks, the generative work of research, reading, and writing happens increasingly alone, while together we continue to check in about our work and weave a common web of context. We go to older texts Haraway cited and future texts that have cited her. We look her up on YouTube, on Ticktock, on Instagram, to see how she is and what she’s up to now. We look for texts that don’t directly mention Haraway but seem to be about her ideas and write about them. We look up news articles about robots, climate change, and women’s collectives. Often, I will divide up the class into smaller groups to consider a few thematically disparate readings I have selected in connection to Haraway.5 We listen to snippets of electronic music, watch scenes from Black Panther and Black Mirror, and though each student will each go very far out on their very own paths, always, we return to Haraway’s words, that packet of photocopied pages which becomes entirely marked up and dog-eared for most of us by progression’s end.

Students often struggle to create a draft in a way that doesn’t simply feel like a chain of events (e.g., first I read this, then I noticed this, then I asked this, then I looked up this). Still, we’ve created such webs of sources that it becomes clear we must make real choices about structure. During drafting phase, in the journal writings and short class conversations that begin our class meetings, I turn to prompts about our readers and what they might need as they learn about our ideas and discoveries. We examine closely together Kenneth Burke’s Parlor metaphor, and I ask students to write about a setting—whether online or in real life—where they have experienced something specific Burke describes, namely that they have “put [their] oar” into the “interminable […] discussion” that is happening around them, “so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before” (Burke 1973, 110–11). Together, we note the participants’ urgency to exchange. Students recognize this tenor of conversation sometimes appears in their classrooms, on online forums they read and sometimes participate in, in article comment sections, in family WhatsApp groups. We consider what it might mean for them to craft such a conversation between the sources in their essays. Some of them mention talks about politics they had around family dinner tables, conversations about religion in the Dining Hall. I show my students an image that could be out of a Crate and Barrel catalogue—of a bunch of beautiful airbrushed people of various skin tones gesturing over a table with tea candles, food in ornate dishes with silver serving ware, tea candles. And in the last few semesters I have begun to pair that with an AI-prompted image of cyborgs sitting down to dinner together (Figure 2).

The dinner party metaphor adds a lightness to considerations of structuring an essay for a reader. It’s a fun exercise to imagine an essay as a dynamic conversation, how Haraway begins the conversation while another one guest (or source) dominates, and another offers a controversial retort, and yet another asks for clarification, and etc. Who is rude and who is the peacemaker? Who adds the truly pivotal piece of unexpected evidence? I ask them to create their own dinner party, whether in images or words or some other form. In their reflection on the assignment, many write about the Dinner Party as the thing from the semester that will stay with them. The image invites the students to consider themselves as host of the party. Who will sit next to whom? Where will you put Haraway? What will they talk about? Sex work? Veganism? Sustainable super-cities in the desert? And, most importantly: how do you want to craft this conversation for your reader to keep them interested? To help their understanding?

Towards the end of the progression, students’ questions and all of their writing choices have become their own. They continue to refine their essay through a group workshop meeting with me and two other students, as well as one final peer workshop based on my own evaluation rubric—regarding things like form, signposting research, idea. When finally they turn in their essay, they take some time in class to read over it once more and write me a note about their process of writing it and what they learned, which I read as I evaluate each essay, in turn. As a final group ritual, I also ask them to each choose their favorite sentence from their essay and read it out loud, with no commentary. The run of sentences from each of their mouths might not be essayistically connected, but the echoes are overwhelming. In this way, we create a sort of beautifully cacophonous closing conversation that ties all their disparate essays back together.

The essays students turn in can be complex and meandering like Haraway. Some are sparse in their thinking and representation, but more of them delight and surprise me, as their reader, their teacher. Last semester, this included an essay connecting the digital hustle economy to future feminisms, a project the student claimed made her realize that she wanted to devote herself to studying culture and narrative instead of science. Another writes about new possibilities for ecological cooperation to strengthen communities, a topic also addressed by an engineering student in the Fall, looking at specific examples of adaptation by smaller human communities. Another engineering student, who said she appreciated that our class was the only place she felt supported in discussing cultural and political issues, wrote an essay about the transformative power of the experiences created by popular artists like Beyoncé. The array is exciting, many of them enjoyable to read in their own right, all of them showing a sense of accomplishment.

When I ask students to reflect on this assignment, on how it fits into the semester, they report feeling really proud for writing such a thing, and that they read Haraway in the first place. One student from the engineering school writes, “I have become a stronger writer [...] my analytical skills have improved because of difficult sources.” Another says, “Haraway's ideas required me to move beyond a singular text and embrace a broader array of perspectives. [...]. This shift pushed me to not only gather information but also critically analyze and synthesize it.” This kind of self-reflection feels like some of the best confirmation for the value of our classroom work that I can hope for, and it was anchored by the greater force of the class’s cooperative work with Haraway’s text, which steadied the students’ dizzying recursive movement between research, thinking, writing, sharing, research, writing, steadied the teacher’s dizzying dance of thinking that your students need you, then that they are getting it, that you are guiding them through, and all you have to do now is find the right moment to let go.

You will write an essay to build your own rich argument by considering thoughtfully chosen evidence from a number of sources. Your final idea will show your reader a new way of thinking or a course of action based on your own thinking/connecting/questioning, and source choices. You will base your essay around considering and reconsidering specific concepts and references that come up in your reading of “A Cyborg Manifesto,” by Donna Haraway. Following research will lead you to new knowledge regarding your question/problem and your focus. Your resulting essay will significantly engage with the first two texts (Haraway, plus an additional “larger conversation” text), as well as at least three additional texts from your own searching; one must be a scholarly (or peer-reviewed) text, and one should be an object, innovation, or other aesthetic text (total essay length: 7-9 pp).

As a group, we will begin by reading “A Cyborg Manifesto” by Donna Haraway and proceed to “How Algorithms Rule Our Working Lives” by Cathy O’Neil, “Mestizaje” by Alicia Arrizón, “The Mother of All Questions” by Rebecca Solnit, and other reader texts of your choosing from our e-reader.5

Reading and re-reading, representation plus context, textual conversation, research to create argument/idea, presentation, drafting, workshopping, and revision.

In addition to all we learned in the last progression, we will practice research, considering audience and context, and re-envisioning our ideas.

You will be graded based on our three basic criteria -- (1) representation -- as related to how concepts and references come from your sources and lead your reader through your thinking, as well as what new knowledge your research yields (2) problem, argument, idea -- as related to how you communicate your initial question/problem and connect the parts of your research and progress towards an overall idea that is unique to you and this essay (3) structure and convention -- as related to how you work with beginning, middle, and end, as well as your acknowledgement of sources

Of course, there’s ample scholarship on the relationship between reading and writing; Bazerman’s ((1980)) framing of the relationship as conversational, involving “reacting” and “evaluation” (p. 659), feels particularly apt.↩︎

If printing isn’t favorable, teaching it as a PDF can work too.↩︎

A term that comes from paired-term concepts, which many in EWP learned about from Ben Stewart, who was the technological wunderkind of our program and with us for decades before absconding out to California after the Spring 2018 semester.↩︎

Although paired-term concepts might be particular to EWP, many scholar/teachers have, of course, devised techniques for teaching reading as part of teaching writing (see, for instance, Carillo 2009, 2016; Sprouse 2019; Wenger 2019).↩︎

My intention in presenting them with a group of essays I’ve chosen at this point in the writing process is for them to practice making connections between seemingly disconnected texts. As Haraway has already led us through class conversations about feminism, racism, intersectionality, planned obsolescence, and being killed off by robots, there is some leeway here for them to play around with conceptual connection.↩︎

This is a sample selection. I adjust these each year depending on current cultural conversations and student interests.↩︎