Abstract: This article describes and reflects on experiences teaching students to compose a Writing Process Photo Essay in the context of an upper-division college writing course that satisfies a campus-wide writing requirement. As the culmination of a quarter-long student inquiry into their own writing processes, this multimodal assignment asks students to combine text and images to help them reflect on the environments, tools, habits and routines that surround their writing activity. This assignment takes its inspiration from calls for renewed scholarly attention to material and embodied aspects of writing process. In the end, this assignment creates opportunities for students to recognize, reflect, and reimagine their own writing activity in school contexts and beyond.

The Writing Process Photo Essay is a multimodal assignment I developed for an upper-division, undergraduate writing course. Its purpose is to provide students a means to engage with their writing processes through documentation, description, and critical reflection. The essay itself is a culmination of my students’ quarter-long inquiry into their own writing processes, not just in terms of drafting and revision, but also with particular attention to the situated nature of their writing, including material environments and tools, as well as embodied habits and routines. In the weeks leading up to this assignment, students collect photographs (and screencaps) of their activity as they work on other writing projects for the course. They also complete a series of exercises designed to help them identify aspects of their writing activity they might want to discuss. Finally, students combine selected images, captions, and approximately 500-750 words of prose to compose a multimodal photo essay formatted like the student sample in Figure 1.

I have assigned the Writing Process Photo Essay in the context of an upper-division undergraduate writing course in the University Writing Program (UWP) at the University of California, Davis. This course, designated as UWP 101: Advanced Composition, satisfies one of two campus-wide writing requirements, the other being a lower-division, first-year writing course (typically, UWP 1: Introduction to Academic Literacies). It is worth noting that UWP 101 is only one of multiple options for students to satisfy the upper-division writing requirement, such as other UWP courses focused on writing in specific disciplines or professions. Sections of UWP 101 tend to be structured around themes developed by individual instructors, though each section is expected to fulfill program-wide student learning outcomes. One of the outcomes relevant to the Writing Process Photo Essay is the expectation that students will (according to the UWP website) “improve their ability to manage the writing process to suit the task and situation, including more advanced skills in planning, drafting, revising and editing” (“Student Learning Objectives | UWP” n.d.).

I have organized my sections of UWP 101 around the theme of “writing in a digital age.” In this course, students create and maintain blogs in which they research and write about a single topic of their choosing over a ten-week quarter. My overall aim in the course is to help students engage critically and responsibly in digital spaces by reframing their work as what Richardson (2010) refers to as “connective writing,” or writing that engages with what other people have said about their topics (p. 28). The aim of this work, as in more traditional forms of academic writing, is to read critically, participate in an ongoing conversation, and use what others say as an opportunity to develop their own ideas. Through this kind of research and connective writing, students learn not only the specific conventions of blogging, but also develop rhetorical awareness and skills that transfer more generally to academic writing and beyond, like how to engage in sustained inquiry and how to situate oneself in larger, ongoing conversations.

Within the context of this course, the final Writing Process Photo Essay culminates a quarter-long reflective inquiry into students’ own writing processes. That inquiry begins with an exercise inspired by Prior and Shipka’s ((2003)) research method of having academic writers draw their writing processes as a means of “tracing the contours of literate activity” (p. 3). Here is the prompt I give students for this exercise:

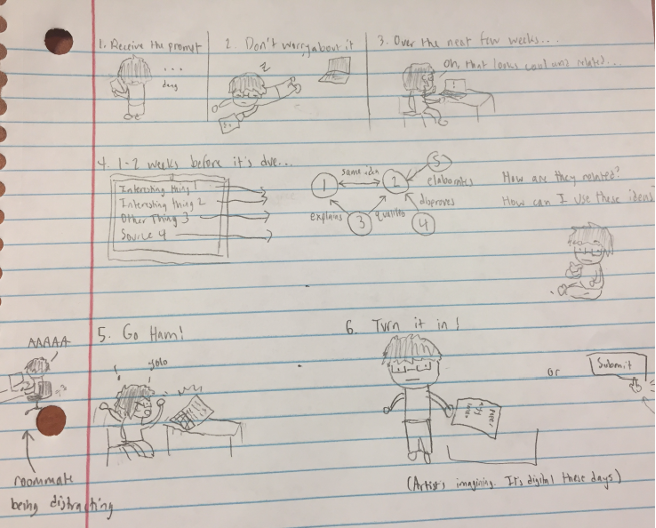

On a single page of paper, make a drawing that represents the typical process you follow when you write for an academic context. Think of papers you have written in previous courses or the blog posts you have written for this course, and consider how you might render that visually in a drawing. Since a “process” is something that happens over time, you may want to consider how to represent that in your drawing. A timeline, map, flowchart, or even a series of panels (as in comics) might work.

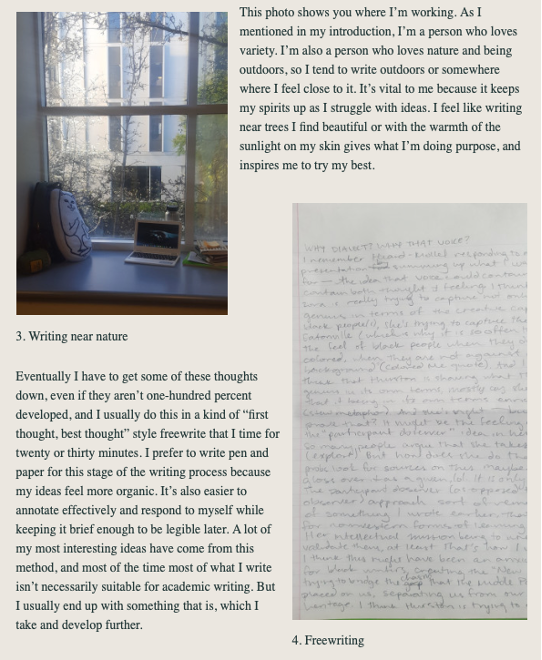

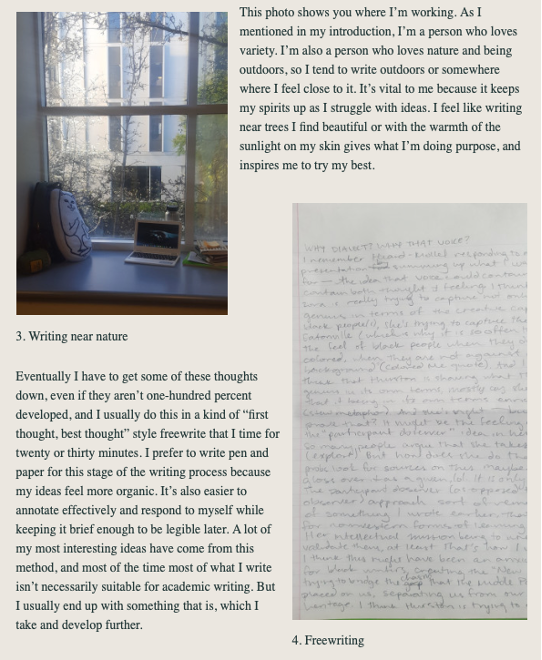

I also encourage students to consider the material conditions of their writing activity, such as the time of day, physical environment, and tools and objects in their surroundings, as well as the habits, routines, or rituals they typically engage in as they compose. Once students have completed these drawings, they share and discuss them in small groups, looking for patterns of commonality or noteworthy contrasts to share with the whole class (see Figure 2 for a sample drawing of a student’s writing process).

At the end of this activity, I direct students to begin collecting photographs or screencaps of their writing processes for the remainder of the quarter (usually 4-6 weeks). I purposefully leave what qualifies as “their writing process” open to interpretation; though when we discuss the drawing exercise, I urge students to think of writing processes in broad terms. In early iterations of this assignment, I asked students to collect these images individually and compile them at the end of the quarter. However, in order to extend their engagement with process over more of the quarter and gain insight into the processes of others, I have more recently had students post images to the social media platform, Instagram. Students create a separate account for this purpose (to avoid having to share their existing accounts, if they have them), and I ask them to post and comment on other students’ posts each week. By sharing their own images and commenting on those of others, students gain a wider view of the range of the practices, environments, and tools that surround writing.

Finally, as we near the end of the quarter, I have students look at previous students’ Writing Process Photo Essays, and we spend time discussing the features of the form and what students consider effective (or not) in them. I then ask them to make a plan for their own essays, noting which images they want to include and which aspects of their writing processes they want to describe and reflect on.

The Writing Process Photo Essay was inspired in large part by recent calls in the field for renewed attention to writing processes. Though process pedagogies arguably continue to dominate writing instruction, just as they have for decades, Takayoshi (2018) argues that “by 1995, composing process research had almost completely disappeared from the field’s official journals” (p. 554). The problem with this neglect, as Takayoshi sees it, is that “a lot has changed in the world of writing since composing process research last captivated our field” (p. 552), but our understandings of it have failed to keep pace. Similarly, Rule (2018) points out that, even as writing studies scholars increasingly focus on writing’s situatedness, embodiment, and materiality, such interest has not manifested itself in the “study of situated material-embodied processes” (p. 404). In other words, even as we were theorizing writing “on massive scales,” the field has “left the material terrain and choreography of writing on a micro-level, or process scale, mostly unexplored” (p. 408).

This scholarly neglect has implications for teaching and learning. Fife (2017) argues that students need opportunities to “notice and reflect on how they structure their composing environments,” and that without this kind of work, students may have trouble developing “a conception of their practices that they can access in order to consciously adapt them.” Moreover, in her more recent book, Rule (2019) suggests that traditional approaches to teaching process rely too much on prescriptivist “a priori strategies,” rather than engaging students in detailed description of situated writing activity (p. 19). In order to demonstrate why such work might be worthwhile, Rule (2018) describes a research project in which she had graduate student writers document their writing spaces through drawings and video recordings of their writing sessions and then reflect on these artifacts in interviews. Through description and reflection on these representations, her students came to recognize how objects like beverages, furniture, and pets not only set the scene for their writing, but also significantly shaped their processes. Together with Prior and Shipka’s ((2003)) study of writers’ processes through drawings and Wyche’s ((1993)) study of her students’ writing habits and routines, this work convinced me as a teacher that my own students could benefit from such description and reflection.

In developing this assignment for my own students, I knew I wanted them to use representational artifacts to spur reflection. However, I worried that asking students to record video of their writing sessions, as Rule (2018) did with graduate students, might prove burdensome and overwhelm my undergraduates with too much information. In the end, I adapted Rule’s ((2018)) approach by having my students take photographs of their writing spaces and use those images as starting points for description and critical reflection. Such documentation and curation has the potential to render material and embodied practices as visual artifacts that can in turn be used to elicit concrete details and insights into composing processes. That is to say, the point of starting with images is to ground their analyses in the concrete. Because my students would collect photographs to document their writing processes and then combine those images with reflective writing, I settled on framing the assignment as a “photo essay,” even though its purpose is not to learn the generic conventions of that particular form. Instead, the writing process photo essay provided a platform for the kind of documentation, description, and reflection that I hoped would help students better understand the impact of materials and environments, habits and routines on their writing activity.

One of the primary challenges of teaching this assignment has to do with timing. The first time I taught it, I positioned the assignment late in the term, as part of a final portfolio unit focused on compiling and reflecting on students’ work over the quarter. The problem with this timing, though, was that students had little opportunity to pay attention to their writing processes throughout the quarter and collect images. My eventual solution to this problem was to introduce the assignment much earlier and have students do the drawing exercise around the third week of a ten-week quarter, so that they had more time both to notice patterns in their writing activity and to collect relevant images. As a result, the assignment and related exercises form a kind of metacognitive thread through most of the quarter, rather than a discrete unit. Combined with my more recent decision to have students post their images on Instagram, I have found that the final photo essays collect more varied images and more nuanced reflection on students’ writing processes.

Another early challenge was settling on a format for the Writing Process Photo Essay. Because my students were already blogging for the course, I had them create a page on their blogs specifically for the assignment. Initially I thought this made sense, because blogging platforms make it relatively easy to combine text and images. However, with the first batch of submissions, I found that some blog templates and methods of displaying images worked better than others. For example, a number of students formatted images of their writing processes as a slideshow displayed at the top of a blog page, with reflective text below the slideshow interface. As a reader, I found it challenging to engage with these submissions because the relationships between the images and text were confusing to ascertain. In a subsequent quarter of teaching the assignment, I asked students to review several samples of the Writing Process Photo Essay from this early quarter, and (without explicit prompting) they identified the slideshow-formatted samples as unnecessarily confusing. Since that point, I have students review the different formatting options within the blogging platform, and we discuss rhetorical strategies for effectively interweaving text and images.

On the whole, students respond positively to the assignment, indicating both on the assignment itself and in course evaluations that they appreciate the opportunity to reflect on how they write. One common sentiment in the essays is the idea that students had not previously given their writing processes much thought, such as one student who wrote that “before the course, I wasn’t aware I had a writing ‘process’.” Nevertheless, many students manage to gain valuable insights or discover surprising aspects of their writing processes as a result of composing the essay. Some learn that they were more creatures of habit than they realized, such as one who was struck by “how much of a routine this [process] has become for me.” Such reflection can provide the opportunity, as Yancey (1998) puts it, “to theorize from and about our own practices, making knowledge and coming to understandings that will themselves be revised through reflection” (p. 6). For example, one of my students wrote that, as a result of paying attention to how she composed, she noticed a habit she was not particularly happy with:

Rereading my sentences over and over again, and making sure every sentence is right before I can move on to the next, drags out my writing process. This would probably be the thing that I would change, and one that I have actually started to do!

By attending to how she wrote, this student noticed a pattern with her composing process, attached meaning to that pattern (as slowing her productivity), and developed a plan for changing her practices.

Part of my hope for this assignment was to make the situated nature of writing activity more visible to students, and in that regard, it has been largely successful. While nearly all students discuss various strategies they use for brainstorming, outlining, freewriting, revising, and editing, the vast majority also attend to the “where and with what” aspects of their writing activity (Rule 2018, 425). Among other things, students mention where they write (e.g., kitchen tables, library carrels, coffee shops), times of day they tend to write (typically evening or nighttime), and the tools they use (e.g., laptops, notebooks, search engines). Beyond that, students often discuss the challenges of maintaining their attention and motivation to write amid various distractions and feelings of anxiety, and strategies they use to get the work done. Chief among these is creating an environment that is conducive to writing, though what that means differs significantly from writer to writer. Some discover that they prefer quiet and solitude, while others seek the noise and energy of busy places or listening to music. Students also frequently mention the importance of taking breaks from writing by doing such things as exercising, watching videos, or preparing a meal.

Perhaps one of the more surprising results of this assignment has been the degree to which students discover, through reflection, that much of what they did not consider writing actually contributes to their composing processes. Some come to realize the importance of taking breaks, such as the student who wrote that “the breaks I take in between are when I do some of my most critical thinking about my topic, so I can take less time to actually draft.” Another student wrote about becoming aware of the need to “balance work and play,” elaborating that

I never really considered those extra activities a part of my writing process before. It wasn’t really until now that I noticed that I do them so often and with such consistency that they actually do form part of my writing process.

Many students write about how things other people might consider distractions, such as music, scented candles, or a television on in the background, actually seem to prevent them from feeling anxious or provide them with energy to continue writing. In this way, one of the more promising outcomes of this assignment is the way in which it helps students recognize existing practices, attach new meanings to them, and develop plans for future writing activities.

I consider this assignment to be a work in progress. Though it does seem to help students describe and reflect on their composing processes, I would like to see them engage even more in identifying practices they might want to change, experiment with different strategies, and reflect on how those changes shape their writing activity. One way to do this would be to have more frequent opportunities for students to share their practices with one another. Therefore, in future iterations of the assignment, I intend to increase the amount of collaboration among students as they collect and begin to analyze images of their writing processes. By sharing images with one another, and comparing their approaches to writing, I hope they might, as Rule (2019) puts it, “start seeing differences in processes, to see others’ conceptions and experiences alongside their own” (p. 209). That is to say, my hope is that, in seeing these differences, students can move beyond treating their writing processes as a static set of practices to be described and reflected upon, toward a view of process as dynamic and contingent on context. It may also be beneficial along these lines to have students document and consider their composing processes across different kinds of writing tasks, both academic and otherwise, such as text messages and social media posts.

Another way to highlight differences in material and embodied composing processes in particular would be to have students encounter similar assignments across the curriculum, beyond courses that satisfy traditional writing requirements. In other words, I can imagine adapting the Writing Process Photo Essay for writing in the disciplines courses, where the aim is to teach students how to write, for example, like a biologist or engineer or historian. Such courses often highlight for students key differences in disciplinary generic conventions, but students might also benefit from opportunities to consider how composing processes might differ as well. Such engagement may help students recognize how different audiences, purposes, and genres might call for different practices. For example, writing processes in some disciplines might include time spent collecting and analyzing data, while others might benefit from drafting earlier in the process. Again, the aim would be to move students from a static view of composing processes to one which values flexibility and having a range of strategies to tackle varied writing tasks.

One final future development to this assignment would be to add a third stage beyond description and reflection, and that is experimentation. I intend to reposition the Writing Process Photo Essay as a waypoint to something more like an intervention in which students use their reflections to identify an aspect of their writing activity to experiment with and then report the results. For instance, they might try writing in a cafe instead of the library, using Google Docs instead of Microsoft Word, or writing for longer (or shorter) sessions. They may also work on mapping different environments or tools onto different kinds of writing tasks, such as using notebooks for freewriting. Along the way, students could reflect even more explicitly on the relationship between different writing tasks and the material conditions of the work. Such tinkering might best be done on low-stakes (or non-academic) writing tasks. The eventual aim would not be for students to codify a specific writing process, but rather to develop the flexibility to adapt their composing practices to different contexts and rhetorical situations.

Whether or not you think of yourself as having a “writing process,” you do. That is, you have a process you go through whenever you write, even if that process changes every time. It’s more likely, though, that there are practices and activities that you tend to do each time you write, and this assignment aims to get you to reflect on them. Doing so is a first step to considering what aspects of your writing process are working well, and which you might consider changing in the future. For this assignment, you will compose a photo essay that combines text (approximately 500-750 words total) with photos to illustrate your process.

As you prepare for this assignment, you will need to take photos (or screencaps) that capture different aspects of your writing process. You should aim to have at least ten photos or images to include in your photo essay. Here are some questions to consider when compiling your images:

What activities do you engage in as you write? How does the writing start? How does it end? What are the steps in between?

Consider the environment(s) in which you typically write. In what settings or contexts do you write, and when you write, who or what is there with you?

How do you do the writing? What tools and technologies do you use when you write?

What are some of the habits, routines, or rituals you typically engage in as part of your writing process?

What kinds of activities, environments, tools, or routines not typically considered “writing” are part of your process?

A photo essay combines text and photographs into a single composition. For this photo essay, you will need to arrange your images onto a page that you create on your WordPress blog. Use at least ten images, but be selective; more isn’t necessarily better. Also, consider what order makes the most sense for your images, and how to arrange them on the page. You may intersperse text with the photos, or you could write a single reflection at the end of the photo essay (if you do this, provide short, descriptive captions for each image).

In your text, your main task is to describe and explain the writing process represented in the images. You should also address the following areas:

What activities do you engage in as you write? How does the writing start? How does it end? What are the steps in between?

Consider the environment(s) in which you typically write. In what settings or contexts do you write, and when you write, who or what is there with you?

How do you do the writing? What tools and technologies do you use when you write?

What are some of the habits, routines, or rituals you typically engage in as part of your writing process?

What kinds of activities, environments, tools, or routines not typically considered “writing” are part of your process?

How typical is this of how you normally write? In what ways do you deviate from this process?

What do you consider part of your writing process that you left out or was hard to represent?

How well do you think this process works for you? In what ways are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your typical writing process?

What would you change about your typical writing process, if you could?

This assignment will be evaluated according to how it...

Represents your writing process through images.

Describes and explains your writing process in text.

Reflects critically on your writing process.

Fife, Jane. 2017. “Composing Focus: Shaping Temporal, Social, Media, Social Media, and Attentional Environments.” Composition Forum 35. http://compositionforum.com/issue/35/composing-focus.php.

Prior, Paul, and Jody Shipka. 2003. “Chronotopic Lamination: Tracing the Contours of Literate Activity.” In Writing Selves, Writing Societies: Research from Activity Perspectives, edited by Charles Bazerman and David R. Russell, 180–238. WAC Clearinghouse. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2003.2317.2.06.

Richardson, Will. 2010. Blogs, Wikis, Podcasts, and Other Powerful Web Tools for Classrooms. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Corwin.

Rule, Hannah J. 2018. “Writing’s Rooms.” College Composition and Communication 69 (3): 402–32.

———. 2019. Situating Writing Processes. WAC Clearinghouse.

“Student Learning Objectives | UWP.” n.d. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://writing.ucdavis.edu/academics/student-learning-objectives/.

Takayoshi, Pamela. 2018. “Writing in Social Worlds: An Argument for Researching Composing Processes.” College Composition and Communication 69 (4): 550–80.

Wyche-Smith, Susan. 1993. “Time, Tools, and Talismans.” In The Subject Is Writing: Essays by Teachers and Students, edited by Wendy Bishop, 1st ed., 111–23. Boynton/Cook.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. 1998. Reflection in the Writing Classroom. Utah State University Press.