Abstract: This paper discusses a first-year writing research prospectus prompt designed to support first-year undergraduate students transitioning from high school writing---which often focuses on summary and synthesis---to college-level writing. In college, ``research papers'' often require knowledge production: developing research questions that address gaps in existing scholarship. My prospectus prompt offers a scaffolded structure for writers embarking on such college-level projects, and it also offers a tool to facilitate writing transfer, with the goal of enabling students to develop major research projects independently in other classes. It does so in two ways. First, it labels the components of major research projects (e.g. objects of study, research questions about those objects of study, and the theoretical frameworks used to analyze objects of study). Second, it provides a process for approaching research projects, including showing students how to develop research questions and how to move beyond summarizing and synthesizing other scholars.

This paper introduces a first-year writing (FYW) research prospectus designed to teach first-year undergraduate students how to move beyond high school research reports into college level writing. In college, “research papers” often require knowledge production: developing research questions that address gaps in existing scholarship. My prospectus prompt offers a scaffolded structure for writers embarking on such college-level projects. More importantly, it facilitates writing transfer by identifying the components of major research projects and making visible how such projects are developed: how to develop research questions, and how to move beyond summarizing and synthesizing other scholars. The assignment’s goal is to enable students to develop such projects independently in later classes. While this article focuses primarily on a FYW prospectus prompt, I conclude by discussing a graduate version that I have used to guide graduate students in fields ranging from forensics to literature.

When I first began teaching FYW, the students’ final research projects were well-organized, well-documented recitations of other scholars’ work on massive topics like “gun control.” Essentially, my first-year college students were continuing to engage in summary and synthesis, the most common forms of high school writing (Beil et al. (2007), p. 7; Rounsaville et al. (2008), p. 102-103). In those early classes, I identified two problems: 1) students did not know how to narrow their projects, and 2) students did not know how to move beyond summary and synthesis of existing scholarship.

Several colleagues came to my rescue. First, Rachel Riedner suggested I shift from discussing paper “topics” to “objects of study.” As I eventually came to define these terms in my prompt, a topic is a “broad and general issue that can be studied.” An “object of study” is any narrowly defined “object” being studied. Examples of an “object” include an utterance, a written or visual text, a political or historical event, an actual object, person, or a group. More specifically, Shakespearian plays are a broad topic; King Lear is an object of study. Political protests are a broad topic; the Westboro Baptist Church visiting George Washington University in 2010 to protest the “gay-friendly” campus is an object of study. This language gave me a way to show students how to narrowly define projects for any subject/discipline.

Second, my colleague Mark Mullen introduced me to theoretical “lenses”: scholarly conversations through which to analyze objects of study. I eventually named such scholarly conversations “frameworks.”1 Some frameworks focus on specific theories, like feminist theory. Others cluster within disciplines, like psychology. Applying a framework to an object of study generates research questions. For instance, the Westboro Baptist Church protest, to which straight students responded by organizing a counterprotest, could be analyzed through a free speech framework: Given the harm the protest might have caused some students, should that protest have been banned, or was allowing the counterprotest (“more speech”) the better choice? Alternately, a different framework such as allyship raised different questions: While straight students tried to serve as allies to the campus gay community, did the straight students overstep allyship bounds by organizing the counterprotest without consulting the George Washington University gay community? Each “framework” raises different questions about the object of study.

These two components—an object of study and theoretical frameworks—became the basis of my research prospectus prompt, along with a third component, research questions. A new problem emerged, however. Former students repeatedly emailed me because they did not know how to transfer what they had done in my class to other college classes. As Inoue (2019) described, “Getting students in a program or classroom to produce a certain kind of written product does not mean that anyone has learned anything in particular. It means they have been able to reproduce a certain kind of document in those circumstances . . . [We do not know] whether students can or will be able to transfer what they learned to future contexts” (p. 149). I did know: my former students were telling me they could not develop college-level research projects without me.

Two of my colleagues, Phil Troutman and Mark Mullen, proposed using a research prospectus. I was skeptical. Like many academics, I first encountered the prospectus genre—also called a proposal—as a graduate student. Here is how the conversation with my dissertation advisor went:

ME: You want me to write what?

ADVISOR: A prospectus.

ME: What’s that?

ADVISOR: A document that describes what your dissertation will be about.

ME: You want me to describe something I haven’t yet written??

My advisor was not alone in her struggles to explain this genre. The prospectus is, to use Swales’s ((1996)) term, an “occluded” genre, one that exists “to support and validate the manufacture of knowledge,” but that—because it operates behind the scenes—is often not a genre writers encounter until they have to write in it (p. 46-7).

Several college writing handbooks, which often target first-year writers, include brief introductions to “research proposals.” However, these handbooks simply tell students to “outline a specific research question and/or hypothesis, and describe how you would go about answering the question” (Miller-Cochran, Stamper, and Cochran 2018, 271–72) or “Your objective is to make a case for the question you plan to explore” (Hacker and Sommers 2016, 408). The assumption is that students already have their questions. For many students just beginning their research, however, the challenge is not explaining why a question is important, but rather how to develop a question that interests them.

I decided to assign a prospectus as a scaffolding step before the major research project. Unlike the college handbooks, however, my prompt establishes the groundwork for students to construct research questions. The prompt provides a space to identify, research, and sift through possible frameworks to apply to the object of study, thus helping students visualize different potential research questions. It gives students a way to imagine—and then choose—the frameworks and questions that most interest them. The prompt also makes visible the process students are following, so they can reproduce and adapt it later.

Research on writing transfer—the process of students adapting writing skills and knowledge learned in one context to a new context—has shown such transfer is difficult to achieve (Beaufort 2007; Bergmann and Zepernick 2007; McCarthy 1987). Recent research, however, offers models that help teach writing transfer: writing about writing (Bird et al. 2019; Downs and Wardle 2007), teaching for transfer (Yancey, Robertson, and Taczak 2014), and genre-based approaches (Devitt, Reiff, and Bawarshi 2004; Driscoll et al. 2020; Tardy 2016). My FYW research prospectus prompt aligns itself with these models by giving students the vocabulary and explicit writing knowledge to facilitate writing in new contexts. If the goal of FYW is to prepare students for college-level, academic writing, then I want my students to leave FYW knowing the components from which academic scholarship is constructed, so that they can succeed in future writing contexts without me.2

In terms of institutional context, the FYW curriculum at George Washington University uses theme-based courses, taught by multi-disciplinary faculty who either teach FYW via their home disciplines, or who select cross-disciplinary themes to teach college-level research and writing. The course themes I use are often cross-disciplinary. For instance, the FYW theme I have taught most frequently is profanity. Students have written research papers on profane utterances that drew upon research in the social sciences, business, the humanities, and law. More recently, I used the prospectus prompt to scaffold a FYW research paper grounded in the social sciences, where students conducted interviews and surveys of college writers, which they then analyzed using theoretical frameworks from writing studies, psychology, and education. The approach to “theoretical frameworks” that I teach is most closely aligned to how scholarship is shaped in the humanities and social sciences, and thus is most likely to transfer successfully to future college courses in those disciplines. At the end of this article, however, I also discuss how the prompt attempts to build a bridge to future writing in the sciences and business.

In the following sections, I describe how I launch the assignment and student responses. I conclude with plans to use the prospectus in a graduate student “dissertation boot camp.”

The FYW version of the prospectus is divided into three sections,3 one for each of the three components already discussed: 1) object of study research, 2) “theoretical framework” research where specific “theory sources” are summarized, and 3) research questions. I begin teaching the prospectus by having students read an introduction to the assignment vocabulary.4 I define “frameworks” as scholarly conversations. I show examples of how scholars working within a field read and cite each other: I label individual articles or books within such scholarly conversations “theory sources.” The “theory source” concept is borrowed from Bizup (2008), although Bizup used the term “method” source, a label derived from the “methods” sections of social science and science articles. Bizup defined such sources as those “from which a writer derives a governing concept or a manner of working” (p.76). Based on reviewer feedback for this article, this year I replaced Bizup’s social science-based label with “theory” sources because it better matched the humanities-based projects my students were engaged in. “Theory” sources provide my FYW students with intellectual tools that help them shape their analysis, evaluation, and/or interpretation of their object of study. I ask students to envision each individual theory source as part of a larger scholarly conversation; I call that conversation a “theoretical framework.” For example, one theoretical framework explores how people from historically dominant groups can work in allyship with historically minoritized groups. A specific “theory source” within that broader framework is K.R. Kraemer’s ((2007)) article on allyship, which my class used to analyze the Westboro Baptist Church visit. I need both terms because in order to find specific theory sources via library database searches, students have to be able to describe and conceptualize the broader conversation—the theoretical framework—within which the theory sources they hope to find are situated.

I do not show students the prospectus prompt until after they have decided upon their object of study, and after they are comfortable with the assignment’s concepts and terms. Students research and write several one-page, pre-writing assignments, each exploring a possible object of study, and share one of those assignments with the class. To learn what theoretical frameworks are, the full class—seventeen students—devotes approximately ten minutes toward helping each peer brainstorm possible frameworks that might intersect with the proposed object of study. For instance, one student wrote about a U.S. soccer player caught yelling the f-slur at a ball boy who dropped a ball. For a framework, the student explored scholarly research on homophobia in team sports. This framework helped the student develop a question about the part played by that soccer player’s straight identity, in a professional soccer context where only one professional player had thus far come out as gay. A different framework—on branding—later generated different questions focused on Major League Soccer’s response to the incident.5

In the process of generating ideas, students learn to shape research questions about the object of study, via the frameworks they propose. This full-class brainstorming requires four classroom sessions, but the repetition provides important practice of new conceptual moves: imagining possible theoretical frameworks that might intersect with an object of study, brainstorming possible database search terms for the frameworks, and seeing the different research questions each framework can potentially generate.6

Only after students have selected their objects of study and identified at least one possible theory source do they read the prospectus prompt. At that stage, the only new term/concept is the requirement to include and define a “keyword”; I explain it by pointing to articles where scholars define keywords in ways that shaped their arguments. When students read the prospectus prompt, I emphasize that the prospectus is not a traditional essay: there is no thesis, no introduction, no transitions, no conclusion. It is more of a heavily segmented, intellectual exercise with subheadings than what students recognize as a “paper.” I convey that segmentation in part by presenting the assignment as a chart (which also serves as the grading rubric). I also have students read a sample prospectus, provided with permission by a former student. As homework, each student prepares three questions about either the prompt or the sample; in class, we discuss those questions until students fully understand the genre expectations.

One of my goals as a teacher of academic writing is for students to learn that academic research contributes to conversations on an object of study. A student learning to produce knowledge usually engages in two steps:

Familiarize themselves with current conversations about the object of study to enable identifying gaps in the scholarship, what Swales (1990) called finding a “niche.”

Identify and apply the analytical tools (the “theory sources”) that will shape analysis.

Within my FYW course, there is not time for both steps. My prompt thus creates an automatic scholarly “niche” for students’ research projects by requiring objects of study that are too new to have been the focus of any published scholarship. For instance, in my profanity-themed FYW class, most students write about a public, profane utterance from the past eighteen months. We discuss the approximate time it takes to publish scholarly articles and books—longer than eighteen months—so that students understand why no scholarship yet exists on the utterance they have selected.7 Students hesitate at this point: they have been trained to distrust “non-academic” sources such as newspaper articles, YouTube videos, or Twitter comments. Because scholarship does not yet exist on their objects of study, however, I point out they will have to use non-academic sources. I tell students that they will be the scholars to open conversations, to contribute new scholarship on their chosen objects of study.

To ensure that students understand not all research has to be entirely “new,” on the last day of the semester, I introduce students to the literature review genre. Doing so helps students see that scholars explore existing research before launching into new projects. Literature reviews allow scholars to gauge what current or relevant research—and what gaps in that research—exists for “objects” that have been well studied (such as Shakespeare’s King Lear), as well as those that have not (their projects on recent profanity).

By already creating the scholarly “niche” that students will fill with their research, my prospectus prompt emphasizes the second step for producing authentic scholarship about an object of study: learning how to identify and apply relevant scholarly frameworks. For the prospectus, students find two or three specific journal articles or book chapters (“theory sources”), and summarize them, one paragraph each. By separating “framework” research from “object of study” research, the prompt makes it structurally impossible for students to engage in pure summary/synthesis.

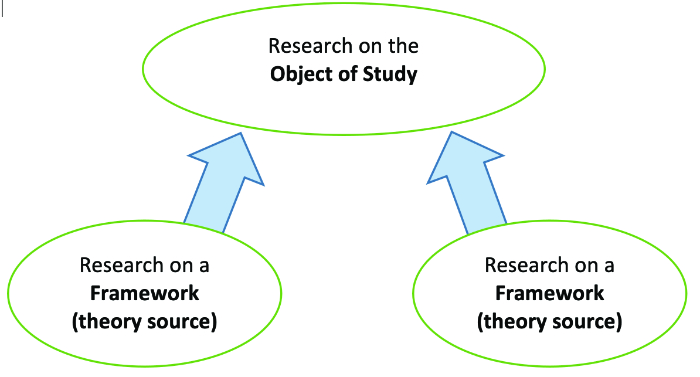

In class, I illustrate this point with whiteboard diagrams, represented in the figures. Figure 1 shows a high school research report, where students summarize and synthesize research on an object of study. Because students only research the object of study, their writing can only repeat what other researchers have written.

Figure 2 shows a college-level research project, where students research an object of study, but also select theory sources that never mention the object of study. In their writing (represented by the blue-filled arrows), students do the intellectual work of applying theory sources to the object of study. This structure makes pure summary and synthesis impossible.

The prospectus also shows writers how to develop research questions. The questions that the students develop must be about the object of study. Next to each research question that students frame, the prompt demands that they also name the theory source that will help them answer that question. This structure enables professors to engage in productive dialogue with students about their research questions. Without a prospectus, professors are stuck asking a question to which students often don’t have an answer: “What are your research questions?” With a prospectus, professors can instead ask a sequence of facilitative questions:

“What frameworks exist that might intersect with this object of study?”

“Which of those frameworks raise questions that interest you?”

“What questions about the object of study will this specific theory source help you answer?”

While students who write strong prospectus drafts are well positioned to outline and write final projects, the prompt is perhaps most valuable for students who do poorly initially because it facilitates productive dialogue, based on the questions above. In end-of-semester self-assessments, students often comment that they plan to borrow and adapt the prospectus structure as a planning tool for future major papers.

Given the humanities-influenced research projects in my profanity-themed FYW course, students leaving my course are well situated to transfer what they learned into “near transfer” humanities contexts (Perkins and Salomon 1988). Students moving into science or business contexts, however, will be faced with “far transfer,” that is, the need to abstract the essence of a skill or knowledge to apply it in a new context (Perkins and Salomon 1988). To address this limit, in the “Introductory Overview” to the prospectus I include a section entitled, “Disciplinary examples of how ‘theory’ sources work.” There, I give “theory source” examples from the sciences, social sciences, business, and humanities. In the humanities, “theory sources” provide an analytical tool with which to examine an object. In the sciences, “theory sources” provide the foundation for the researcher’s methodological choices, which the “Introductory Overview” describes as “an experimental method which you [the researcher/student] might then borrow [from a scholar] to conduct your own experiment.” Both Bizup (2008) and I see these intellectual moves as the same—a source providing “a governing concept or a manner of working” (p. 76)—but I admit the abstraction level is high for students outside the humanities. I thus talk students through this section of the prompt, linger over the examples, and return to those examples in individualized ways as I find out students’ planned majors. To prevent possible negative transfer, with each major paper I ask students to also reflect on their writing in other courses, asking what FYW concepts and skills they have been able to use—and which concepts and skills have not applied. I emphasize that writing in new disciplinary contexts demands that students determine what writing strategies are not appropriate in the new context, as well as which concepts will transfer.

For graduate students, I add a literature review requirement to the prompt, so students explore existing research on their object of study. In cases where literature reviews do not make visible a “gap” that a thesis or dissertation could address, the framework section becomes key. For such students, finding “theory sources”—scholarly sources that do not discuss the object of study—helps overcome the anxiety of influence (Bloom 1973). For instance, one graduate student studying literature felt she was simply repeating, rather than adding to, the conversations surrounding her object of study. Adding a framework section to her prospectus pushed her to locate two or three scholars not directly engaged in her object of study, but whose work provided a theoretical framework through which to analyze her object of study. The process also enabled her to understand and articulate how her line of analysis differed from that of other scholars.

Unfortunately, almost all dissertation advice books, many of which include chapters on writing proposals, currently focus on disciplines outside the humanities. Only a small handful offer more general advice targeting all graduate students (Bolker 1998; Dunleavy 2003) or writers in the humanities (Clark 2007; Semenza 2010). Moving forward, I hope to develop the graduate version of my prospectus prompt by partnering with my college’s writing in the disciplines program and writing center to develop a stand-alone workshop, and eventually a one-week “dissertation boot camp.” Providing graduate students—particularly in the humanities, where the prospectus genre tends to be the least explained—with explicit instruction about the genre’s purpose and scaffolding structure could potentially save months (perhaps years) of dissertation time. The humanities-shaped terminology of the FYW version of the prompt adapts well for humanities graduate students. With further adaptations—such as shifting terminology from “theory sources” to “method sources” and the addition of an explicit “methodology” section, this prompt could also become the basis for graduate students in the sciences and business. Ultimately, a prospectus should facilitate productive dialogue between students and faculty, and provide a structured process that supports students, at any level, as they learn to become producers of knowledge within their fields.

For your major research project this semester, I will ask you to develop an argument about an object of study: a specific, profane utterance.

To develop your research project, you will engage in two steps:

STEP ONE: Write a Research Prospectus (Paper #2) A prospectus is a planning document that will help you structure your initial research on your project as you make decisions about a) which object of study you want to focus on, b) which scholarly tools you want to use to analyze that object of study, and c) which research questions you want ask about that object of study.

STEP TWO: Write the Final Research Project (Paper #3): The final project is where you’ll answer the research questions you’ve posed about your object of study, drawing on the scholarly sources you identified in the prospectus.

A paper topic is a broad and general issue that can be studied and analyzed. For instance, the general use of the term “bitch” by comedians is a topic. In contrast, an object of study is a single instance within that broader topic: it’s a specific utterance, embedded in a particular context—such as a single usage of the word “bitch.” For your final research project (and the Research Prospectus leading up to it), you might write about a politician’s use of “fuck” at a specific fundraiser, about a specific performance where a comedian used a racial epithet, about an athlete’s use of the f-slur toward a referee during a specific game. What all these instances have in common is that they are individual moments—a particular moment at a particular time and place where an individual speech act occurred.

Center your paper on an object of study that focuses on a specific, profane utterance. That utterance may be part of a public event that has been reported on in public forums (newspapers, magazines, blogs, news websites, etc.), or it may be something you said or experienced (i.e., personal experiences are allowed for this paper).

While your object of study will focus on a specific, profane utterance, that speech act may have provoked a response or several responses. For instance, when Dick Cheney uttered “fuck” on the Senate floor in 2004, there were a slew of responses. As the writer, you would choose the responses that seem most relevant to your project and include them in your object of study to research and analyze. In other words, your “object of study” will be a specific event which will probably include not only the profane utterance, but also the response(s) to that utterance.

The goal of this paper is for you to contribute your voice as a scholar to conversations regarding your object of study. In order for you to do so, you must choose a moment when profanity was used that has not been written about by other scholars. If you choose a widely-publicized object of study that took place over 18 months ago—such as Dick Cheney’s 2004 use of “fuck” on the Senate floor—there is a very good chance that some scholar somewhere has already written about that object of study. Your paper would then turn into a report on other scholars’ analyses of the profane utterance. That’s not the assignment.

To ensure that there is space for your voice in the scholarship on your object of study, you should do one of three things:

Write about a small, local instance where a profane utterance was reported on publicly (in local newspapers, a local blog, a local news source), but that remained a local news item, rather than a national or international item. For instance, when the (all Black) Washington, DC, Dunbar high school football team went to play a game against the (largely White) Maryland Fort Hill high school team and the “N-word” was allegedly used against the Dunbar team players, the local DC press picked up the story—but it remained a local news item, unreported on a national scale. If you go with this option, you may pick any instance, whether contemporary or historical, to work with. To find this type of object of study, you may want to focus on local or historic newspapers.

Write about an instance where a profane utterance was reported on publicly in the national and/or international press, but restrict yourself to utterances that took place in the past 18 months (i.e., since April 20XX). Given the publishing timeline of most scholarly publications, it usually takes 18-24 months before scholars respond to and analyze such public incidents in their articles and/or books. Thus, if you restrict yourself to utterances that have taken place since April 20XX, you’ll be inserting your voice into the conversation before that conversation gets fully started (so there will be intellectual space for you to develop your own line of analysis and argument).

Write about a personal experience that involved yourself or a close friend/family member. Because you’ll be writing about a personal experience, you’ll obviously have a clear field for writing: no published scholars will have written about this object of study, so you’ll be the one doing the intellectual work of contextualizing it, analyzing it, and developing your own line of argument.

For the purposes of this class, your object of study must be an instance of profanity. The term “object of study,” however, can be used in other contexts, for other assignments. It usually refers to a specific person (i.e., a specific political figure, athlete, or musician), group (i.e., the hacker group, “Anonymous”), event (i.e., a political assassination, a specific market crash, a specific experiment or case study), object (i.e., a specific novel or film), or place (i.e., Times Square). You may find it useful to think about this definition more broadly, so that you can start looking for “objects of study” in the scholarly articles you read, as well as the future papers that are assigned to you during your time at GW.

“Theory” sources are scholarly texts that provide writers with the intellectual tools needed to analyze, interpret, or evaluate events, places, objects, phenomena, groups, or people (i.e., to help writers discuss their objects of study).

Disciplinary examples of how “theory” sources work:

In the sciences, a “theory” source might be an article in Science that explains how to conduct an experiment in microfluidics—an experimental method which you might then borrow to conduct your own experiment.

In the social sciences, a “theory” source might be an article explaining how a certain study was conducted (i.e., how to establish intercoder reliability)—an experimental method you could borrow to conduct your own study.

In business, a “theory” source might be Adam Smith’s theory of economics—and you might draw on his theory to help you analyze your object of study (such as a recent federal decision about regulating banking practices).

In the humanities, a “theory” source might be a feminist scholar whose work will help you analyze anything from a recent film to a Shakespearean play.

Scholars—the people who produce “theory” sources—write to other scholars in their field: they read and cite each other to make visible their conversations. In disciplines within the humanities, those conversational networks are often referred to as “theoretical frameworks,” “intellectual frameworks,” or “scholarly lenses.”

To find a useful “theory” source, you have to identify the scholarly conversation taking place--the “theoretical framework” that houses that conversation. Such conversations sometimes cluster around a specific theory. Think of Adam Smith’s theory of economics, which has generated and shaped a number of scholarly conversations, or think of feminism or Marxism. These are theories that have engaged a number of scholars. In selecting such a theory, your task would be to familiarize yourself with several of the main voices within a particular theory and to decide which of those sources to adopt as the “theory” sources that would best help you analyze your object of study.

Or, you may choose to take a more disciplinary approach. Scholarly conversations are often clustered within disciplines and sub-disciplines, such as linguistics, anthropology, psychology, sociology, literature, history, economics, biology, architecture, etc. Again, these are disciplines that have engaged a number of scholars. In selecting such a discipline, your task would be to familiarize yourself with several of the main voices within a particular discipline (or, more probably, a particular sub-discipline, such as the study of Hip Hop within African American Studies; or child development within psychology) and then select from among those scholars the specific “theory” sources that will best help you analyze your object of study.

In addition to finding a framework (scholarly conversation) to engage with for your object of study, our course readings will provide you with a second possible framework: profanity. In our class, we’ve read scholars who are engaged in conversations with each other (witness how Stephens cites Pinker; how Seizer cites Douglas). Given that your objects of study must focus on an instance of profanity, almost all of you will draw on one or two course readings as “theory” sources contributing to those “framework” conversations on profanity.

The theory sources that you select are what will guide your approach to your object of study and determine the kinds of research questions you’ll ask. These theory sources will provide you with the tools to develop you own voice, your own analysis, your own critical inquiry into and interpretation of your object of study. Your use of these theory sources will push you beyond simply repeating what others have said about your object of study (writing a “report” on it), to adding to that conversation.

25% of your final grade

A 1500-1750 word prospectus, formatted in MLA style, double-spaced, 12 point font, Times New Roman or Arial. Please include your final word count (not including the Works Cited page) in parentheses after the final paragraph of the paper.

Works Cited page: This page should include at least two scholarly sources found through the library’s electronic subscription services and the book catalog. At least one of these sources must be a book. The Works Cited page should also include several object of study sources (which may be newspaper articles, websites, blogs, etc).

| Finalize object of study and explore possible frameworks | Wednesday, [DATE] |

| Workshop drafts are due at your individual conferences with me: | |

| —Individual Conferences | Monday, [DATE] |

| —Individual Conferences | Wednesday, [DATE] |

| —Individual Conferences | Friday, [DATE] |

| Final drafts due in class | Monday, [DATE] |

A “prospectus” is a genre commonly used to establish the intellectual parameters of major projects, such as honors theses or capstone writing projects. A prospectus is also useful, however, for long research papers, as it will help you delineate the major aspects of your project before you sit down to write the paper. It’s a trouble-shooting tool that allows you to test out the different parts of your project at an early stage—before you’ve committed a massive amount of time to researching and writing—to see whether you’re likely to hit a dead end, and whether the lines of research you’re following are leading to the kinds of research questions you’re actually interested in exploring.

College writing asks you to add your own voice to scholarly conversations. To do so with credibility and authority, you need to give yourself analytical tools. “Theory” sources will provide you with the criteria/tools/lenses to develop your own analysis about your object of study. Your research on your object of study and “theory” sources must be completely separate: you may not draw on the same sources for these different parts of your research. Because your theory sources will be completely different from your sources for your object of study, you will have to do the intellectual work of applying the theory sources (your analytical tools) to the information and narratives that you’ve gathered about your object of study. In doing so, you will develop your own analysis/interpretation/ evaluation of the object of study.

Finally, the prospectus helps prepare you for the moment when you develop the “research questions” that will structure and guide your final paper. The task of the final research paper will be to answer these questions. “Research questions,” as defined by this prospectus, are open-ended. That is, they are interpretive, evaluative, analytical, or argumentative questions (i.e., questions that cannot be answered with a “yes” or “no,” and that cannot be answered just by looking up factual information). These questions should arise from your theory sources but should be articulated in terms of your object of study (i.e., the questions should be about your object of study).

This prospectus will be formatted in a series of individual sections that will be set apart from one another by subheadings. The subheadings that you’ll use are given in the chart below. After each subheading, you’ll write one or more paragraphs, giving however much information is needed to respond to that prompt (without, of course, exceeding the set page limit for the assignment). You may decide to combine several of the subheadings or change the order of the entries. For instance, some of you may prefer to begin by describing the background context for your object of study, before introducing the object of study itself. Others will choose to merge the “keyword” section into the “theory sources” section. That’s fine, but please do include all the relevant subheadings for any given section.

Below is not only the prompt to which you’ll be responding for this analytical portion of the assignment, but also the rubric that I’ll be using to grade the paper.

(Editors’ note: The author’s assignment is represented here in paragraph form. As the author has noted above, however, students receive it in the form of a table. The Supplementary Materials available online present the assignment in its original formatting.)

The object of study identifies a specific, profane utterance, along with any relevant responses. In this section of the prospectus, you’ve brought in enough information to introduce your object of study to readers unfamiliar with it.

Begin by naming the framework (scholarly conversation) within which your “theory” sources are situated. Then introduce two or three “theory” sources within that framework (most students devote a separate paragraph to each theory source). Where appropriate, research debates within the framework and select theory sources that represent alternative/oppositional perspectives. Your description of each theory source should address readers unfamiliar with it and follow the “SCaD” process, where you include a Summary of the source, Contextualize a quotation from the source so that readers can understand the quotation as we’re reading it, and Discuss the quotation (showing your readers what you want us to see in the quotation). Your handling of the “theory” source should be detailed enough that by the time I finish reading about each theory source, I should be able to see how it will help you develop your analysis of your object of study.

Your “theory” sources for this section should have been found through the library’s services and MUST be one of the following types of sources:

scholarly journal article

book

legal case

Your “theory” sources must explore different information/ideas (i.e., two “theory” sources explaining that trash talk is beneficial in the heat of a game would be redundant)

Include one or two italicized sentences (but not more) at the end of each SCaD paragraph that briefly applies that theory source to a specific aspect of your object of study, to show the line of analysis you plan to use the theory source to develop in the final paper.

Target length = Approximately 2 pages

At the beginning of this section (which can be a bullet-pointed list of questions), re-name the scholarly framework from which the questions will arise.

Present at least three questions—more, if possible—from the named framework

Name (in parentheses next to each question) the theory source(s) that will help you answer that particular question.

The questions MUST be articulated in terms of your object of study because your paper is about the object of study, not your theory sources.

At least one major set of debates should be visible in your questions.

NOTE: “Research” questions are open-ended questions that invite analysis, interpretation, or argument about your object of study. The work of your final paper will be to answer those questions.

Definition: Keywords are words that you, as the researcher and writer, plan to explicitly define in your final paper in order to shape how your readers think about those terms.

Devote one full paragraph to defining a keyword

Cite at least one scholar (and possibly more) to help you establish your definition (“scholar” means you need to draw on scholarly journal articles, books, or legal cases). Introduce your source, draw upon a quotation to help you define the keyword, and explicate the quotation.

Make visible to the reader (explicitly or implicitly) why you picked this keyword (i.e., why giving it a precise definition matters to your project)

TIP: Do not cite a dictionary definition or encyclopedia (including Wikipedia). Doing so would signal to your reader that you’re not an expert on this topic—and that’s a problem in a research paper. Instead, cite the scholars you’ve been reading: use these definitions to make visible the range and depth of your research to your readers. A potential exception to this rule is profane words. For instance, while a number of scholars have provided definitions of the “n-word” and “bitch,” it’s very difficult to find scholars who provide definitions of the f-slur or “gay.” If you are struggling to find a scholarly definition for one of your keywords, talk to Prof. Hayes about it.

NOTE: Not a subheading—this is a grading criterion

NOTE: Not a subheading—this is a grading criterion

PERCENTAGE OF FINAL GRADE: 35%

This paper will bring together all of the work you have done this semester. It should present, in beautifully worded prose, a provocative, complex, and persuasive argument about an object of study that focuses on a specific, profane utterance. Contextualize that utterance in order to make visible the impact of the rhetorical situation on the word/phrase as it was used in that particular time and place.

Your argument about this object of study should…

Be grounded in the research you have done on your object of study;

Include whatever background context your readers will need to understand your argument fully;

Be shaped by your exploration of theory sources drawn from at least one framework;

Make visible the exigency for writing this paper (the immediate, pressing need for the intervention you are making in the conversation surrounding your object of study).

NOTE: This essay is not an extended summary of (or report on) your various sources. Instead, it is your opportunity to make an original contribution to the conversation surrounding the object of study that you are examining.

2500-3000 words, double-spaced lines, one-inch margins, 12 point font, Times New Roman or Arial. Number the pages. Please include your final word count (not including the References page, DO include the title page and abstract in the word count) in parentheses after the final paragraph of the paper.

References (APA format) with a minimum of 8 sources, including at least three scholarly sources. At least one of the three scholarly sources must be a book; at least one must be a scholarly journal article.

Beaufort, A. 2007. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Utah State University Press.

Beil, C., and M. Knight. 2007. “Understanding the Gap Between High School and College Writing.” Assessment Update 19 (6): 6–8.

Bergmann, Linda S., and Janet Zepernick. 2007. “Disciplinarity and Transfer: Students’ Perceptions of Learning to Write.” Writing Program Administration 31 (1-2): 124–49.

Bird, Barbara, Doug Downs, I. Moriah McCracken, and Jan Rieman, eds. 2019. New Directions for/in Writing About Writing. Utah State University Press.

Bizup, Joseph. 2008. “BEAM: A Rhetorical Vocabulary for Teaching Research-Based Writing.” Rhetoric Review 27 (1): 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350190701738858.

Bloom, Harold. 1973. The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry. Oxford University Press.

Bolker, Joan. 1998. Writing Your Dissertation in Fifteen Minutes a Day: A Guide to Starting, Revising, and Finishing Your Doctoral Thesis. Henry Holt and Company.

Clark, Irene L. 2007. Writing the Successful Thesis and Dissertation: Entering the Conversation. Upper Saddle River, NJ; London: Prentice Hall.

Crowley, Sharon. 1991. “A Personal Essay on Freshman English.” Pre-Text: A Journal of Rhetorical Theory 12 (3-4): 155–76.

Devitt, Amy J, Mary Jo Reiff, and Anis S Bawarshi. 2004. Scenes of Writing: Strategies for Composing with Genres. San Bernardino, CA: Pearson Longman.

Downs, Douglas, and Elizabeth Wardle. 2007. “Teaching About Writing, Righting Misconceptions: (Re)Envisioning ‘First-Year Composition’ as ‘Introduction to Writing Studies’.” College Composition and Communication 58 (4): 552–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20456966.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, Joseph Paszek, Gwen Gorzelsky, Carol L. Hayes, and Edmund Jones. 2020. “Genre Knowledge and Writing Development: Results from the Writing Transfer Project.” Written Communication 37 (1): 69–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088319882313.

Dunleavy, Patrick. 2003. Authoring a PhD Thesis: How to Plan, Draft, Write and Finish a Doctoral Dissertation. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ericsson, K. Anders. 2006. “The influence of experience and deliberate practice on the development of superior expert performance.” In The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance., edited by K. Anders Ericsson, Neil Charness, Paul J. Feltovich, and Robert R. Hoffman, 683–703. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gorzelsky, Gwen, Carol L. Hayes, Ed Jones, and Dana Lynn Driscoll. 2017. “Cueing and Adapting First-Year Writing Knowledge: Support for Transfer into Disciplinary Writing.” In Understanding Writing Transfer: Implications for Transformative Student Learning in Higher Education, edited by Jessie L. Moore and Randall Bass, 115–21. Stylus Publishing.

Greene, Stuart. 2001. “Argument as Conversation: The Role of Inquiry in Writing a Researched Argument.” In The Subject Is Research: Processes and Practices, edited by Wendy Bishop and Pavel Zemliansky, 145–64. Boynton/Cook Publishers.

Hacker, Diana, and Nancy Sommers. 2016. Rules for Writers. 8th ed. Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Inoue, Asao B. 2019. Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom. Perspectives on Writing. Fort Collins, Colorado: WAC Clearinghouse.

Kellogg, Ronald T., and Alison P. Whiteford. 2009. “Training Advanced Writing Skills: The Case for Deliberate Practice.” Educational Psychologist 44 (4): 250–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520903213600.

Kraemer, Kelly Rae. 2007. “Solidarity in Action: Exploring the Work of Allies in Social Movements.” Peace & Change 32 (1): 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0130.2007.00407.x.

McCarthy, Lucille Parkinson. 1987. “A Stranger in Strange Lands: A College Student Writing Across the Curriculum.” Research in the Teaching of English 21 (3): 233–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40171114.

Miller-Cochran, Susan, Roy Stamper, and Stacey Cochran. 2018. An Insider’s Guide to Academic Writing: A Rhetoric and Reader. Bedford/St. Martin’s.

Perkins, David, and Gavriel Salomon. 1988. “Teaching for Transfer.” Educational Leadership 46 (1): 22–32.

Rounsaville, Angela, Rachel Goldberg, and Anis Bawarshi. 2008. “From Incomes to Outcomes: FYW Students’ Prior Genre Knowledge, Meta-Cognition, and the Question of Transfer.” Writing Program Administration 32 (1-2): 97–112.

Russell, David R. 1995. “Activity Theory and Its Implications for Writing Instruction.” In Reconceiving Writing, Rethinking Writing Instruction, edited by Joseph Petraglia, 51–77. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Schwartz, D. L., J. D. Bransford, and D. Sears. 2005. “Efficiency and Innovation in Transfer.” In Transfer of Learning: From a Modern, Multi-Disciplinary Perspective, edited by Jose P. Mestre, 1–52. Information Age Publishing.

Semenza, G. 2010. Graduate Study for the 21st Century: How to Build an Academic Career in the Humanities. 2nd ed. Palgrave Macmillan.

Swales, John M. 1990. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. Cambridge Applied Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 1996. “Occluded Genres in the Academy: The Case of the Submission Letter.” In Academic Writing: Intercultural and Textual Issues, edited by Eija Ventola and Anna Mauranen, 45–58. John Benjamins Publishing.

Tardy, Christine M. 2016. Beyond Convention: Genre Innovation in Academic Writing. University of Michigan Press.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake, Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak. 2014. Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. Utah State University Press.

I adapted this term from Greene’s ((2001)) discussion of “framing” writing.↩︎

There is considerable debate on the role of FYW in American universities. I agree with scholars who argue that what constitutes “good” writing is determined by the disciplines (Crowley 1991), discourse communities (Beaufort 2007), or activity systems (Russell 1995) in which writers work. However, I also agree with writing transfer scholars who argue that FYW can help transition students from high school to college-level writing through attention to writing transfer-enhancing moves (Downs and Wardle 2007; Gorzelsky et al. 2017; Yancey, Robertson, and Taczak 2014).↩︎

When working with graduate students, I add a fourth section to the prospectus: a literature review. For reasons explained later in the article, I exclude a literature review from the FYW version of the assignment.↩︎

In past years, I defined the assignment vocabulary in the final paper prompt, which students read first. Based on reviewer feedback for this article, however, this year I moved the assignment vocabulary (“object of study,” “frameworks”) to a new introductory “overview” of the prospectus and final paper, which worked well.↩︎

With this student’s permission, I have posted their prospectus to my George Washington University faculty web page to serve as a sample prospectus for interested readers. It is also available at part of the Supplementary Materials on this journal’s website.↩︎

For scholarship on the impact of practice, see Ericsson (2006; Kellogg and Whiteford 2009; Schwartz, Bransford, and Sears 2005).↩︎

In the prompt, two other options are presented that allow students to explore objects of study that have not been discussed by scholars.↩︎