Abstract: This article describes and reflects upon a student art project assignment and accompanying issue-advocacy written piece that allows students to explore topics of social justice and environmental sustainability in a business and society senior seminar course. The process of producing art and creative writing allows students to critically reflect on current business ethics concepts that are relevant to their interests. The art is displayed in a gallery exhibit, allowing for further intellectual exploration as students explain their work to others. The learning outcomes of this art project are two-fold. First, students and faculty develop a greater sense of liberatory consciousness, a social identity-shaping mechanism that extends beyond disciplinary boundaries. Importantly, as faculty, we learn a great deal from our students, particularly during the art exhibit. Second, students develop competency in, and a passion for, issue advocacy about important social and environmental issues. Ultimately, this assignment inspires students to become future leaders in professional organizations that are ethical, inclusive, and environmentally sustainable.

The plain fact is that the planet does not need more successful people. But it does desperately need more peacemakers, healers, restorers, storytellers, and lovers of every kind. It needs people who live well in their places. It needs people of moral courage willing to join the fight to make the world habitable and humane. And these qualities have little to do with success as we have defined it (Orr 1991, 54).

How does a business student, instilled with the maxim that profitability is the only viable definition of success (e.g., Devaney 2007; Jensen 2001; Khurana 2010), thrive in a world embodied by the above call for courage? How do we guide students in their fight for a world that is both habitable and humane? Even as corporations and business schools advocate for more ethical, stakeholder-based approaches to business, these same institutions perpetuate logics of efficiency and meritocracy that exacerbate inequality (Amis et al., (2020)). In our courses on business and society, we wrestle with these questions every day. We offer this paper as a reflection on our ongoing teaching journey in addressing the paradox of stakeholder capitalism embedded in current business practice.

In the sections that follow, we describe how we came to introduce liberatory consciousness as a counterpoint to teaching about competitive business strategy. A liberatory consciousness-based lens critiques existing structures and their orientation to inequities, increases awareness of our complicity in such structures, and fosters commitment toward a more equitable and just society (Love 2000). Within this framework, we offer an art-project assignment as a humble antidote. The assignment consists of a student-driven work of art and a supporting creative written piece. Each student creates a social-justice themed art project that is displayed in an art gallery. In the accompanying written component, students explore the topic(s) as a form of personally meaningful advocacy. Student responses suggest that this assignment challenges their default assumptions about business and prepares them to become engaged, questioning citizens with voice and agency.

In reflecting on our own identities as teachers, we find that these art assignments have helped to re-center and clarify our priorities away from the individually centered worldview so common to corporations and business academia, and instead toward a collectivist, societally- and ecologically-focused curriculum (Verbos et al, (2011)). This process helps us as educators to acknowledge the “political, ethical, and philosophical nature” of management education and aims to “bring values into the classroom” (Grey 2004, 180). The students’ artwork renews our awareness, appreciation, and motivation to address systemic and structural inequities. The illustrative examples we provide at the end of this manuscript in Figures 2, 3, and 4 highlight the quality and power of such an assignment, which has implications for teaching social justice in the classroom in the contexts of the global pandemic, climate change, and the George Floyd Uprising against racism.

Business school curricula emphasize management practices that match industry requirements and are driven by industry requests (e.g., Fotaki and Prasad 2015; Ghoshal 2005; Hühn 2014). While these practice-based requirements may change rapidly in accordance with the rhetoric of an efficient, meritocratic competitive marketplace, the underlying inequalities and injustices remain persistent (Amis et al., (2020)). As critical educators, we are heartened by declarations of business leaders who, echoing the words of critical business professors (e.g., Freeman (1984), (1984)), champion the importance of stakeholder-based capitalism1 (Business Roundtable 2019). However, a recent analysis found that those same proponents have done no better than other companies in protecting jobs, labor rights, and workplace safety during the pandemic, maintaining practices that foster racial and gender inequality, and resisting changes for environmental rights (Ward et al. 2020).

This failure highlights the paradox of business education (Bunch 2020). Even when attention is directed toward stakeholder communities, recommended courses of action are often framed within existing metrics and organizational structures that reinforce systemic discrimination. This crisis of legitimacy is highlighted by the economic devastation following the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing movement against racial injustice, both of which have collectively “posed the first test of the lofty words proclaiming a kinder form of capitalism” (Goodman, n.d.). The crisis also exposes the limitations of business school values: efficiency, economic growth, resource-constrained mindsets that drive utilitarian cost-benefit thinking, and a capital-driven marketplace as the preeminent solution to societal ills.

Our reflections suggest that the roots of this paradox lie in a reliance upon a vocational-based curriculum (Reynolds 1999) that, in taking the above values for granted, emphasizes increases in capital accumulation over the development of a liberatory consciousness. The content and process of education both matter in shaping students’ critical thinking about values, their formation of career objectives, and their subsequent career trajectories. While business courses may be well-intended, they are subsumed by a maxim that individual success is the conclusive achievement. The meritocratic and technocratic mindset that success (implicitly economic success) is dependent solely on merit, hard work, and technical competence, ignores inequitable outcomes in society that are byproducts of structural inequality and systemic racism (Bertsou & Caramani, (2020); Chetty et al., (2014)). What does that do to a student’s developmental process? If few opportunities for independent critical thought are presented, the student, eventually a business professional, will rely on the default: profit maximization to the detriment of other societal values (Giacalone and Wargo 2009). More concretely, students who internalize these closely held business assumptions may find themselves actively at odds with the world-changing capabilities needed to respond to stakeholder needs, including awareness of climate change and urgent demands for social justice.

To embrace a liberatory consciousness is to first recognize that the status quo is systemically inequitable. The social movements that protest against systemic racism and unequal treatment of essential workers during the global pandemic recognize, for example, that the status quo is incompatible with equity and justice (Love 2000). As a team of management educators, we understand that structural change is a difficult goal when students (and teachers) are constrained by a doctrine of capital accumulation as the “north star” in all actions. For example, while business students rate “intelligence,” “charisma,” and “responsibility” high among characteristics of worthy leaders, they consistently rate “empathy” and “service” as the lowest desirable characteristics (Holt et al. 2017). A traditional business curriculum is largely incompatible with the values necessary to bring about social justice.

How, then, can we create curricula in service to a liberatory consciousness, where students have the opportunity “to analyze events related to equity and social justice, and to act in responsible ways to transform society” (Love 2000, 130)? How do we guide students toward critical thinking, embedded and embodied within their own experiences of justice and community? Critical thinking, or “reasonable reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do” (Ennis 2015, 32), is a key citizenship skill that students have historically developed in college (Benjamin et al. 2013). Yet, Steedle and Bradley ((2012)) find that among seven primary fields of academic study, business students score among the worst on the Collegiate Learning Assessment Problem Task, an assessment that evaluates critical thinking and writing skills.

Business classes that attempt to develop critical thinking and engage students’ moral consciousness fall at two ends of a spectrum: business and society courses that focus on stakeholders and social responsibility, and service-learning courses that focus on experiential learning through community engagement (Godfrey, Illes, and Berry 2005). However, business and society courses typically emphasize case studies and readings that rely on frameworks that maintain the primacy of current business practice and the centrality of organizational survival. There remains a disconnect between how students understand class material and their personal relationships to organizations in their communities.

While service-learning classes offer first-person experiences (e.g., Grobman, (2017)) that can act as gateways to liberatory consciousness, these courses are hard to scale because of student-faculty ratios, resource priorities, and administrative overhead (Kenworthy-U’Ren 2008). To bridge the gap between classroom learning and active community engagement of service learning, we move toward a critical pedagogy that bridges the chasm between class and practice. An example of our critical pedagogy is a class art project. Art projects offer students an immersive opportunity to bridge critical concepts (e.g., stakeholder management) and the students’ own internalization of collective liberation, human flourishing, and personal and social healing.

What does liberatory consciousness look like in practice? In our experience, it shows up as varied combinations of a fumbling and humbling vulnerability. Instead of structuring courses around values in service to capital accumulation (e.g., utilitarianism and capital growth toward a market society), we grapple with the civic and moral conditions of our curriculum by inviting skepticism into the classroom as well as an earnest co-creation of knowledge with our students (Giroux 2010; Shor and Freire 1987). This critical pedagogy acts in direct support of a liberatory consciousness by creating a dialogue between students and instructors to understand the causes of inequity and injustice (Giroux 2010).

In preparing course readings and assignments, we reflect on whether our course materials center on the values of human flourishing, collective liberation, and societal healing. Human flourishing, for example, is an expansive value that is the basis for student development of moral virtues and reasoning about the wellbeing of humanity (McKenna and Biloslavo 2011). Collective liberation recognizes that we are all bound together in a beneficent mutuality. It is about the liberation of people from vast inequities toward collective human flourishing (Crass 2013) rather than individualized success based on socio-economic privilege or fallible notions of merit (Guinier 2015; Sandel 2020). To value personal and societal healing is to recognize an organization’s duty to restorative and reparative justice, which involves acknowledging and taking responsibility for the harm organizations have caused (Davis et al. 1992). Instances of organizational harm are as recent as the harm that frontline workers have faced during the pandemic, as continuous as the financial industry’s exclusionary and discriminatory lending practices, or as long-lasting as the seizure and occupation of indigenous lands for industrial development.

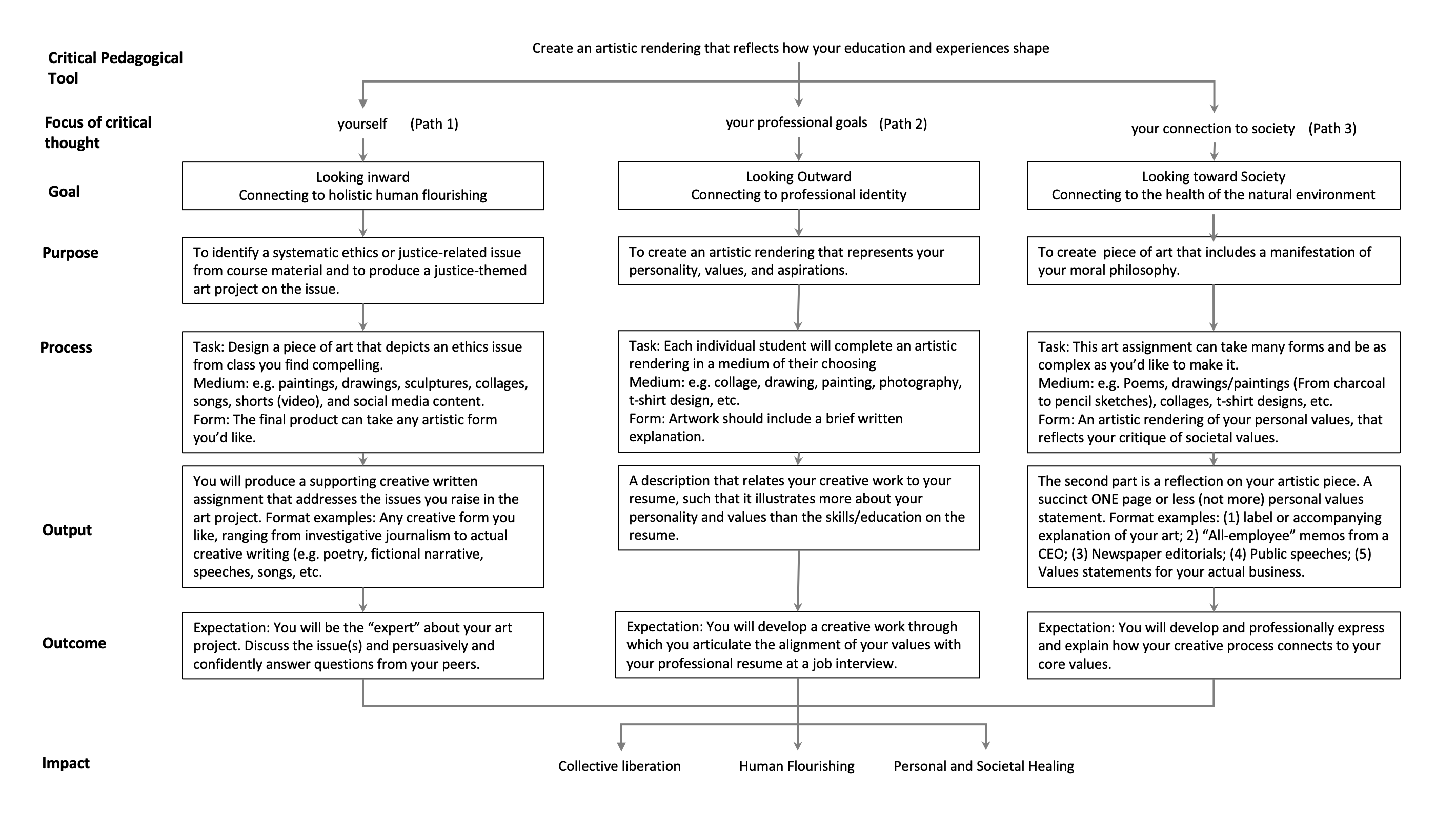

As an example of critical pedagogy in practice, we developed a student art project, Widening Your Lens: Advocacy through Art. This assignment encourages students to interrogate systemic (in)justice within organizations and to explore paths toward more equitable and just organizational power structures where members become bound together in a beneficent mutuality. The project consists of a work of art and a supporting creative written piece. Generally, each student creates a work of social justice-themed art related to course topics. We display this work in an art gallery. The written component is a chance for students to explore topics as a form of advocacy. (See Figure 1 for each of our unique approaches to the process.2)

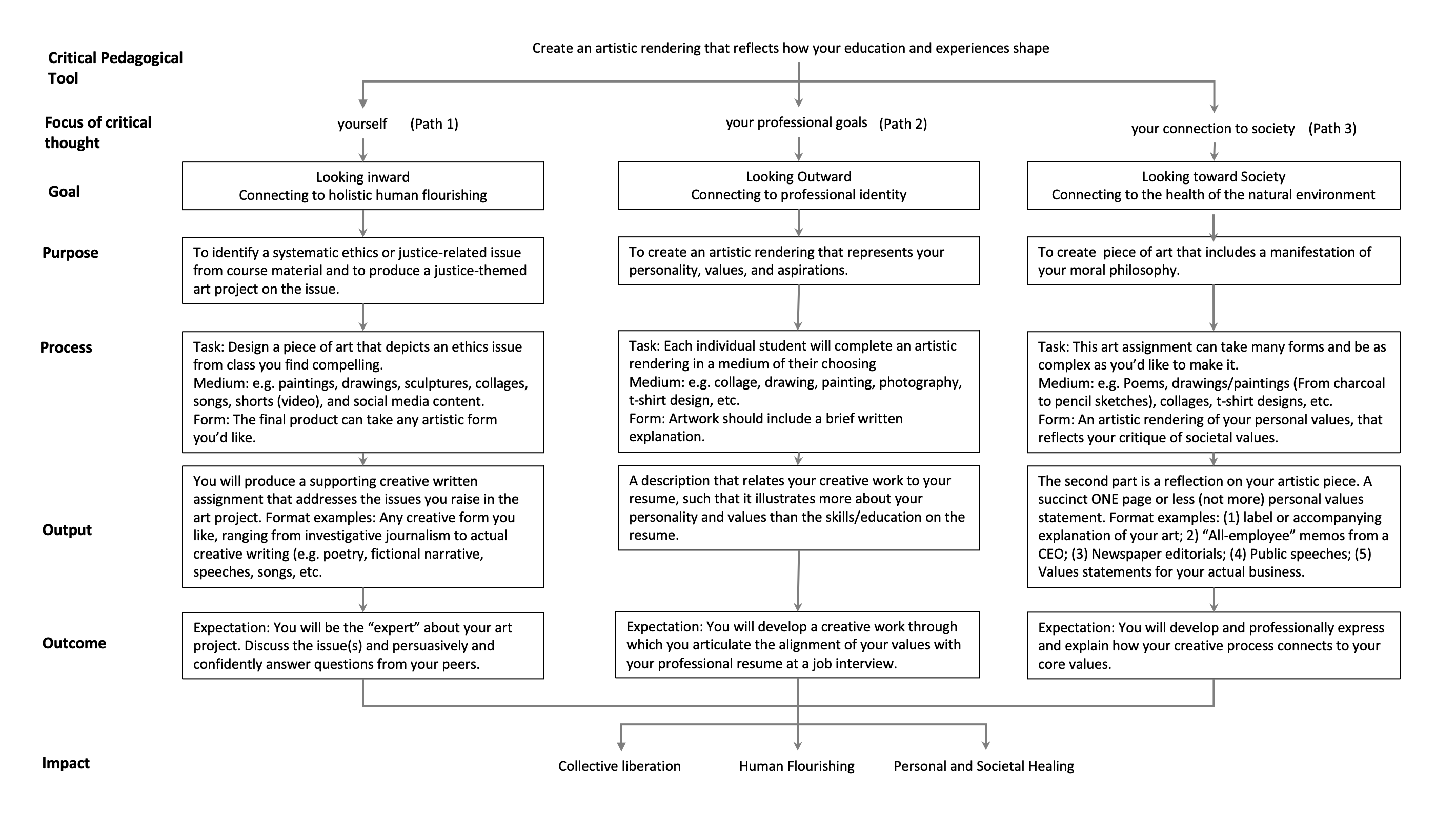

To our surprise, we found that preparing for the art exhibition was itself counter-hegemonic to our prior training in neoliberal educational norms. Such norms dictate that professors deliver knowledge to students as passive receptacles of knowledge (Ayers, Quinn, and Stovall 2009). Even when teaching extended beyond passivity and toward discovery, student knowledge was often evaluated within teacher-centered rubrics and frameworks. We offered pedagogical taxonomies (e.g., Bloom) linearly to our students (Starbird and Powers 2013; Doughty 2006), such that the acquisition and formation of knowledge became a passive act. Instead, our art assignment requires students to take responsibility for each other’s learning. We challenge our students to become experts on the topic of their art so that they can teach others. Learning via an art exhibit is itself a critical pedagogical approach for business students who are otherwise attuned to completing assignments for which grades are easily quantifiable and that are highly individualistic and competitive. Instead, students work collaboratively to develop creative, meaningful projects. Figure 2, for example, became the basis for that class to organically learn about and discuss the construction of gender roles. What is often part of our formal curriculum instead emerged from the students themselves, through collective sensemaking and a liberating mindset.

We found that part two of the project, the written assignment, offers a critical approach to business education in three ways. First, we challenge our students to reject conventional business education goals of objectivity and information sharing to instead embrace values, morality, issue advocacy, and activism (e.g., through such tools as the teaching of ethos, logos, kairos, and pathos techniques). Students respond with impassioned writing about issues they find deeply meaningful. Second, we encourage students to reject typical business-writing formats (reports, case studies, and other informational forms). Students respond by writing creatively, in the form that best conveys their goals and their learning, ranging from investigative journalism to poetry, narratives, speeches, songs, and other forms. Third, we encourage students to explore the acquisition of knowledge not as an accumulation of specific facts but as the deployment of strategies and reflective tools that allow them to acquire, interpret, and make sense of the world. Rather than prescribed expectations of “right” and “wrong,” students feel empowered to develop value-based decision-making frames to guide them as professionals (Arce and Gentile 2015). Students respond by embracing the challenge of becoming experts on topics.

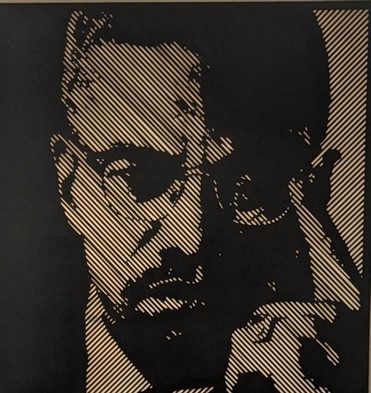

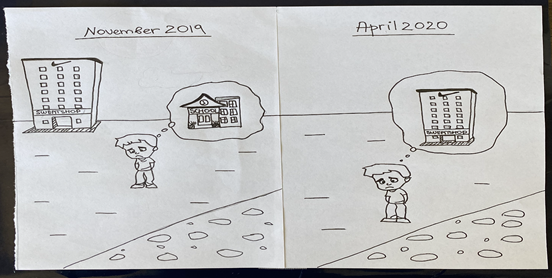

Notably, by taking away the burden of finding “correct” answers to social justice dilemmas, students felt more comfortable expressing vulnerability and uncertainty in their findings. In reflecting on the original paradox that “good” business intentions for stakeholder communities reinforce systemic discrimination upon those same communities, we think that the art assignments help by explicitly replacing strict, preconceived metrics with emergent, community-generated alternatives. Figure 3, for example, titled “Passport to the Future,” allowed for a wide-ranging class discussion about whether housing is a human right, a market commodity, or something else. We found no “right” answer here, only well-developed arguments supported by the teachings of figures such as Malcolm X. Similarly, Figure 4, an art piece titled “Child Labor and Covid 19,” led to deep, student-led critiques of utilitarian arguments in favor of child labor and toward an understanding of education as a human right. In both cases, student learning and contemplation about corporations and human rights was far more robust than would have been the case in traditional management classrooms.

Overall, we have found that our students develop and express a voice as they wrestle with their understanding of systemic causes of, barriers to, and solutions for organizational-based injustice. Students develop critical, systematic explanations for organizational (in)justice, which often run contrary to mainstream business school culture. Students articulate ideas on cooperative economics, reparative justice for historically marginalized communities, and inclusive prosperity. While students embody the values articulated within a stakeholder-based framework, they also hold true to their own communities and to their sense of social justice.

Humans so far have generally deified and aligned with the “king” of the jungle or forest-lions, tigers, bears. And yet so many of these creatures, for all their isolated ferocity and alpha power, are going extinct. While a major cause of that extinction is our human impact, there is something to be said for adaptation, the adaptation of small, collaborative species. Roaches and ants and deer and fungi and bacteria and viruses and bamboo and eucalyptus and squirrels and vultures and mice and mosquitos and dandelions and so many other more collaborative life forms continue to proliferate, survive, grow. Sustain. (brown 2017, 4).

As we write this essay, the global pandemic and the Floyd Uprisings of the summer of 2020 have made business schools across the United States take stock of their priorities, values, and culture, and consider just how seriously they value Black lives. As cisgendered, male, Black, brown, and white professors in business schools, we grapple with the limitations of our own training and the positionality offered by our privilege. Our personal and professional identities are no longer separate and distinct but are reflected in the Black, brown, white, low-income, international, mind-expanding intersectional diversities, hardships, and achievements of our students across the spectrum. The art assignment is a small step in this ongoing journey to become “liberation workers,” educators who “practice intentionality about changing the systems of oppression” around us (Love 2000, 129).

Moving forward, we can do more to make the assignment more liberating. We can, for example, continue to think about student access to art materials. We have considered a class survey of materials needed so that we can secure them ahead of time. We have experimented with having the art project in-class and providing students with basic art supplies (markers, paint, canvasses, glue, for example). We can also think more about incorporating art from students with disabilities, such as those with visual impairments. Though we aim to create a class culture that already provides accessibility (e.g., syllabi and assignment access for students with visual impairments), there is more to do here.

In our exploratory surveys, only eight percent of student responses indicated that the artwork made them think of productive work. This underscores the dichotomy between a social-justice perspective and the pervasive business education framework, in which “productive work” is socialized as something other than human flourishing, collective liberation, or personal healing. This dichotomy begs a deeper question: what does it take for liberatory work to be seen as productive work? And, more compellingly, what does it take for “productive work” in business schools to also be liberatory? As a small example, we need to think about how our preconceptions of productive work—in terms of rigor and quality—are confounded in students’ written issue-advocacy statements. Despite encouraging multiple written formats, we find ourselves conforming to common expectations of written text (e.g., grammar and formatting) that privilege students from higher socioeconomic backgrounds or simply those who are better at writing in the ways we as instructors are trained to evaluate, thereby perpetuating a systemic, structural inequity that is both rigid and outdated. How can we make written formats of the project liberating for students who have been told they aren’t good writers since they were young? How do we allow space for written projects via social media in the same way that we do for traditional essays? Possibilities abound for our personal growth as facilitators of this journey toward greater liberatory consciousness.

Challenges continue as the pedagogical methods in a face-to-face classroom are different from an online social justice pedagogy. Online instruction has historically been antithetical to social justice-based pedagogy, as it has exacerbated gaps in success between students across socioeconomic backgrounds. In particular, Black, brown, and low-income students consistently underperform in online courses (Protopsaltis and Baum 2019). Yet, our reality in education is that virtual learning is inevitable.

Encouragingly, technological advancements and instructor commitment make it possible to embody a liberatory consciousness through assignments such as a virtual Widening Your Lens project. Across our courses, we have implemented a virtual art project in 16 classes with over 500 students since the pandemic forced our university online. We experimented with different online platforms that allow students to present their work to each other virtually. Further, we find that conveying issue-advocacy or activist work virtually through social media platforms is often second nature to our students. Will this take them on different career trajectories or encourage them to act as agents of change? While too early to tell, it is heartening that our students have used the consciousness developed in our classes to change us, their instructors, and to participate in the chorus of voices speaking out against racial and environmental injustice, toward greater, shared humanity.

Path 3 from Figure 1: Create an artistic rendering that reflects how your education and experiences shape your connection to society.

Deliverable: This project consists of:

An artwork that connects a topic from this semester with your own values and ethics.

An artist statement: A one-page write-up of the topical issue, a reflection of how your own values connect to this topic. We will hold an art gallery style exhibition online for the first part of the session in Week 15.

Purpose of Project: a. To develop and express your core values. b. To learn to professionally express and explain ideas.

Theme: Business, Society and the Environment in the time of Covid-19. The coronavirus pandemic has been a complete part of our daily lived lives. From lockdowns and shelter-in-place, to job losses, job changes, family concerns, health concerns, travel concerns, and every conceivable re-allocation of priorities, our world suddenly changed. Online interaction has become more important than ever. The weaknesses of government, the cruelties of business, and the inadequacy of just-in-time global supply chains are made clear when the whole world stops.

At the same time, there have been moments of hope and inspiration. Healthcare and emergency workers work heroically under extremely stressful conditions. Proactive government leadership helped flatten the curve in countries around the world and has taken courage. Proactive business leadership that accommodates employee hardship takes a willingness to look beyond the short term. Many small businesses have shown a deep commitment to their local communities. The rallying cries of protest movements: Black Lives Matter have offered us glimpses into the strengths of individuals, community and a hopeful future.

This semester, we looked at the relationships between business, government, society and the natural environment. Topics included: The Corporation and its Stakeholders. Corporate Social Responsibility. Business and the Local Community. Business and Ethics. Business and Globalization. Business and the Natural Environment. Business and Public Policy. Technology, Society and Privacy. From this vast list of topics, think about a specific topic/concern that resonated with you. How might you showcase your personal values in relation to this topic? How might you represent this topic, and create a personally meaningful work of art?

Part 1 (5%): Part one is an artistic representation of your professional values statement. This piece of art should be a reflection on our class activities/topics so far and should include a manifestation of your moral philosophy. This assignment can take many forms and be as complex as you’d like to make it. By creating an artistic rendering of your professional values, you give your workplace values more thought and take the exercise seriously. The end result can be whatever you’d like it to be. Students have created: Poems, drawings/paintings (From charcoal, watercolors, crayon, to pencil sketches), collages, digital artwork, sculpture, paper-mâché sculptures.

Note: Please use materials you have at home, at your disposal. You are in no way required to go to a store or to purchase additional materials. You can create digital artworks, spoken word pieces, poems, collages, or other forms that utilize the tools at hand.

Deliverable 1: A picture / A video of your artwork to be uploaded to our course LMS by 10:00 a.m. on Tuesday December 1.

Grading Rubric for Part 1: Personal Values Art Project

5 pts: Creativity and time well spent.

3 pts: solid effort, low in creativity.

0-2 pts: half-spirited effort.

This rubric is intentionally centered around ‘effort’ rather than any perception of ‘objective quality.’ In the weeks leading up to the art project, there will be instructor consultations, peer discussions and prototype offerings in small groups, that will help indicate the expected level of effort and thought to be put into your art-project.

Part 2 (5%): The second part is a reflection on your artistic piece. The assignment is a succinct one-page personal values statement. You should cite a specific topic in the text and at least two other reference sources in your reflection. Please use APA format for the citations. The format of the assignment can vary. Students often submit assignments in these forms: (1) a label or accompanying explanation of your art; 2) “All-employee” memos from a CEO; (3) Newspaper editorials; (4) Public speeches; (5) Values statements for your actual business.

Deliverable 2: Your artist statement will be due on our course LMS by Friday December 4 at 5:00 pm.

Grading Rubric for Part 2: Personal Values Statement

5 pts: Professionally written with no spelling/grammar errors. Clear references with citations. Identifies & convincingly articulates two or more moral frameworks to guide decisions.

3 pts: Professionally written, but with spelling/grammar errors. Clear references with citations. Identifies & convincingly articulates a moral framework to guide decisions.

0-2 pts: Unclear, haphazard writing. Spelling/grammar errors. Lacks references with citations. Moral framework guiding decisions is unclear.

Amis, John M, Johanna Mair, and Kamal A Munir. 2020. “The Organizational Reproduction of Inequality.” Academy of Management Annals 14 (1): 195–230.

Arce, Daniel G, and Mary C Gentile. 2015. “Giving Voice to Values as a Leverage Point in Business Ethics Education.” Journal of Business Ethics 131 (3): 535–42.

Ayers, William, Therese M. Quinn, and David Stovall, eds. 2009. Handbook of Social Justice in Education. Routledge.

Benjamin, Roger, Stephen Klein, Jeffrey Steedle, Doris Zahner, Scott Elliot, and Julie Patterson. 2013. “The Case for Critical-Thinking Skills and Performance Assessment.” https://docplayer.net/11412636-The-case-for-critical-thinking-skills-and-performance-assessment.html.

Bertsou, Eri, and Daniele Caramani, eds. 2020. The Technocratic Challenge to Democracy. Routledge.

Bloom, Joshua, and Waldo E. Martin. 2016. Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. University of California Press.

brown, adrienne m. 2017. Emergent Strategy. Chico, CA: AK Press.

Bunch, Kay J. 2020. “State of Undergraduate Business Education: A Perfect Storm or Climate Change?” Academy of Management Learning & Education 19 (1): 81–98.

Business Roundtable. 2019. “Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote ‘an Economy That Serves All Americans’.” Business Roundtable.

Chetty, Raj, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, Emmanuel Saez, and Nicholas Turner. 2014. “Is the United States Still a Land of Opportunity? Recent Trends in Intergenerational Mobility.” American Economic Review 104 (5): 141–47.

Crass, Chris. 2013. Towards Collective Liberation: Anti-Racist Organizing, Feminist Praxis, and Movement Building Strategy. Pm Press.

Davis, Gwynn, Heinz Messmer, Mark S. Umbreit, and Robert B. Coates. 1992. Making Amends: Mediation and Reparation in Criminal Justice. Psychology Press.

Devaney, Michael. 2007. “MBA Education, Business Ethics and the Case for Shareholder Value.” Journal of Academic Ethics 5 (2): 199–205.

Doughty, Howard A. 2006. “Blooming Idiots: Educational Objectives, Learning Taxonomies and the Pedagogy of Benjamin Bloom.” College Quarterly 9 (4).

Ennis, Robert H. 2015. “Critical Thinking: A Streamlined Conception.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Thinking in Higher Education, 31–47. Palgrave Macmillan.

Fotaki, Marianna, and Ajnesh Prasad. 2015. “Questioning Neoliberal Capitalism and Economic Inequality in Business Schools.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 14 (4): 556–75.

Freeman, R. E. 1984. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Pittman.

Ghoshal, Sumantra. 2005. “Bad Management Theories Are Destroying Good Management Practices.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 4 (1): 75–91.

Giacalone, Robert A., and Donald T. Wargo. 2009. “The Roots of the Global Financial Crisis Are in Our Business Schools.” Journal of Business Ethics Education 6: 147–68.

Giroux, Henry A. 2010. “Rethinking Education as the Practice of Freedom: Paulo Freire and the Promise of Critical Pedagogy.” Policy Futures in Education 8 (6): 715–21.

Godfrey, Paul C., Louise M. Illes, and Gregory R. Berry. 2005. “Creating Breadth in Business Education Through Service-Learning.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 4 (3): 309–23.

Goodman, Peter S. n.d. “Stakeholder Capitalism Gets a Report Card. It’s Not Good.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/22/business/business-roudtable-stakeholder-capitalism.html.

Grey, Christopher. 2004. “Reinventing Business Schools: The Contribution of Critical Management Education.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 3 (2): 178–86.

Grobman, Laurie. 2017. “‘Engaging Race’: Teaching Critical Race Inquiry and Community-Engaged Projects.” College English 80 (2): 105–32.

Guinier, Lani. 2015. The Tyranny of the Meritocracy: Democratizing Higher Education in America. Beacon Press.

Holt, Svetlana, Joan Marques, Jianli Hu, and Adam Wood. 2017. “Cultivating Empathy: New Perspectives on Educating Business Leaders.” The Journal of Values-Based Leadership 10 (1): 3.

Hühn, Matthias Philip. 2014. “You Reap What You Sow: How MBA Programs Undermine Ethics.” Journal of Business Ethics 121 (4): 527–41.

Jensen, Michael C. 2001. “Value Maximization, Stakeholder Theory, and the Corporate Objective Function.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 14 (3): 8–21.

Kenworthy-U’Ren, Amy L. 2008. “A Decade of Service-Learning: A Review of the Field Ten Years After JOBE’s Seminal Special Issue.” Journal of Business Ethics 81 (4): 811–22.

Khurana, Rakesh. 2010. From Higher Aims to Hired Hands: The Social Transformation of American Business Schools and the Unfulfilled Promise of Management as a Profession. Princeton University Press.

Love, Barbara J. 2000. “Developing a Liberatory Consciousness.” In Readings for Diversity and Social Justice, edited by Maurianne Adams, Warren J. Blumenfeld, Rosie Castañeda, Heather W. Hackman, Madeline L. Peters, and Ximena Zúñiga, 470–74. Routledge.

McKenna, Bernard, and Roberto Biloslavo. 2011. “Human Flourishing as a Foundation for a New Sustainability Oriented Business School Curriculum: Open Questions and Possible Answers.” Journal of Management & Organization 17 (5): 691–710.

Orr, David W. 1991. “What Is Education for?” In Context, no. 27: 52–55.

Protopsaltis, Spiros, and Sandy Baum. 2019. “Does Online Education Live up to Its Promise? A Look at the Evidence and Implications for Federal Policy.” Center for Educational Policy Evaluation.

Reynolds, Michael. 1999. “Critical Reflection and Management Education: Rehabilitating Less Hierarchical Approaches.” Journal of Management Education 23 (5): 537–53.

Sandel, Michael J. 2020. The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good? Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Shor, Ira, and Paulo Freire. 1987. A Pedagogy for Liberation: Dialogues on Transforming Education. Greenwood Publishing Group.

Starbird, S. Andrew, and Elizabeth E. Powers. 2013. “The Globalization of Business Schools: Curriculum and Pedagogical Issues.” Journal of Teaching in International Business 24 (3-4): 188–97.

Steedle, Jeffrey T., and Michael Bradley. 2012. “Majors Matter: Differential Performance on a Test of General College Outcomes.” In 2012 Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association. Vancouver, British Columbia.

Verbos, Amy Klemm, Joe S. Gladstone, and Deanna M. Kennedy. 2011. “Native American Values and Management Education: Envisioning an Inclusive Virtuous Circle.” Journal of Management Education 35 (1): 10–26.

Ward, B., V. Bufalari, M. Tulay, and S. E. Murphy. 2020. “COVID-19 and Inequality: A Test of Corporate Purpose.” KKS Advisors.

Stakeholder capitalism advocates that business leaders engage with the complex, challenging, and interdependent world of customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and shareholders, rather than focus on shareholder primacy.↩︎

A version of this figure in high-resolution PDF with readable text is available as supplemental material to this article.↩︎